© Anonymous/AP

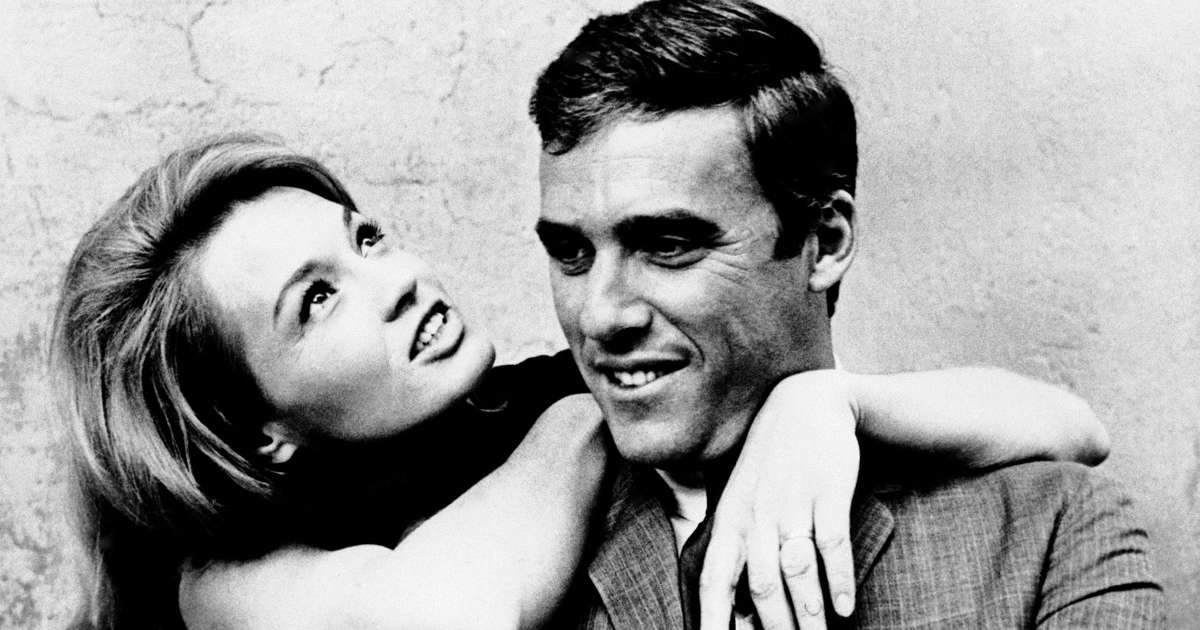

Burt Bacharach in 1965 with his then-wife, actress Angie Dickinson.

Burt Bacharach, a colossally successful pop composer — with more than 70 Top-40 hits — who provided the cocktail party playlist for the swinging ’60s and early ’70s with songs including “I Say a Little Prayer,” “Alfie,” “Do You Know the Way to San Jose,” “Close to You,” “Promises, Promises” and the Oscar-winning “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head,” died Feb. 8 at his home in Los Angeles. He was 94.

His publicist, Tina Brausam, confirmed the death but did not provide a specific cause.

Often teaming with lyricist Hal David, Mr. Bacharach wrote a succession of hits performed by musical torchbearers of the shag carpet era — Aretha Franklin, Tom Jones, Dusty Springfield, Herb Alpert, Sergio Mendes, the Carpenters, the 5th Dimension and especially singer Dionne Warwick.

Mr. Bacharach’s music ebbed and flowed from vogue, but his canon of songs brought him his industry’s highest honors. Much of his most enduring work featured majestic harmonies with abrupt key changes and ornate time signatures drawn from his grounding in classical music and his fervor for bebop jazz. Frank Sinatra once quipped that Mr. Bacharach “writes in hat sizes. Seven and three-fourths.”

Yet the songs remained accessible — “maybe not too sophisticated,” the composer once told the London Daily Telegraph, “but sophisticated enough to have some durability. And not too sophisticated to have you just hear it by some piano-player in a bar.”

More than 1,000 artists have recorded his music, a record placing him squarely in the Great American Songbook tradition alongside Cole Porter, Irving Berlin and the Gershwins.

© AP/AP

Mr. Bacharach accepts the Oscar for Best Original Score for “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” in 1970.

“His harmonic sophistication goes far beyond what record labels or audiences demanded in the 1960s and 1970s,” said Ted Gioia, author of “Love Songs: The Hidden History.” “He had higher standards than almost any of his peers on AM radio. It was a kind of hippie veneer imposed on solidly crafted melodies and rhythms from another era. There was a paradox here, but Bacharach made it work — in fact, he turned it into art.”

“What the World Needs Now Is Love” and “This Guy’s in Love With You” sent the listener floating down a martini river, a gentle current of violins dappled with muted trumpets, where the only occasional brine was a lyric by David.

“What do you get when you fall in love? You only get lies and pain and sorrow,” Warwick sang playfully over an up-tempo rhythm in “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” the 1969 hit that summited Billboard’s Easy Listening chart. When he and David wrote the song, Mr. Bacharach was in the hospital — a setting that inspired the cheeky line, “What do you get when you kiss a guy? You get enough germs to catch pneumonia.”

“I always tried to create songs that were like mini movies,” Mr. Bacharach once said. One of his finest examples was “One Less Bell to Answer,” a massive hit for the 5th Dimension in 1970 in which the singer appears blasé about “one less egg to fry” and “one less man to pick up after” but ultimately reveals her pain — “all I do is cry.”

Mr. Bacharach hit a pop culture peak with “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” a rakish 1969 western starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford as bank robbers on the run. It was one of Mr. Bacharach’s few film scores and won him Oscars for both the score and the instant hit “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head.”

B.J. Thomas sang David’s colloquial poetry (“cryin’s not for me / ’cause I’m never gonna stop the rain by complaining”) over idly strummed ukulele and guitar. The song accompanied Newman’s carefree bike ride with Katharine Ross on his handlebars, an iconic snapshot of Mr. Bacharach’s heyday and good-times ethos.

B.J. Thomas, who sang ‘Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head,’ dies at 78

The hits kept coming. “What’s New Pussycat?,” “Walk on By,” “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart,” “A House Is Not a Home” all entered the cultural bloodstream — as did “(There’s) Always Something There to Remind Me,” which received a Top 10 new wave cover by Naked Eyes in 1983.

Mr. Bacharach shared an Oscar for his theme song for “Arthur” (1981) with lyricist Carole Bayer Sager, his future wife, and singer Christopher Cross. Mr. Bacharach and Sager also wrote “That’s What Friends Are For” for the 1982 film “Night Shift,” a number that became an anthem of the AIDS-awareness movement.

Mr. Bacharach’s musical reputation faded before a renaissance in the 1990s that was sparked by praise from unexpected sources such as the band Oasis, which included a photo of the composer on the cover of its 1994 debut album “Definitely Maybe.”

The jazz pianist McCoy Tyner recorded an entire album of Mr. Bacharach’s music in 1997. The next year, Mr. Bacharach shared with Elvis Costello a Grammy for best pop vocal collaboration for the song “I Still Have That Other Girl”; Costello had previously partnered with Mr. Bacharach on the ballad “God Give Me Strength,” used in the 1996 film “Grace of My Heart.”

The composer was cool again — even if some of his newfound appreciation was laced with irony. He played along, making a winking cameo in the Mike Myers spy spoof “Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery” (1997), playing the piano and singing “What the World Needs Now Is Love” atop a double-decker bus.

When President Barack Obama awarded Mr. Bacharach and David the Library of Congress’s Gershwin Prize for Popular Song in 2012 — the year David died — Myers gave an arch rendition of “What’s New Pussycat?” in a blue sequined jumpsuit.

© Oli Scarff/AFP/Getty Images

Mr. Bacharach performs during the Glastonbury Festival of Music and Performing Arts in Somerset, England in 2015.

Classical to jazz

Burt Freeman Bacharach was born in Kansas City, Mo., on May 12, 1928, and grew up in New York City. His father wrote a syndicated newspaper column about men’s grooming. His mother was an amateur songwriter and piano teacher and directed his classical musical studies.

He was in his teens when he heard trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and saxophonist Charlie Parker wafting over the airwaves. It was “like somebody opened a window,” he told the BBC. He forged an ID card and started frequenting bebop clubs on 52nd Street, a main artery of Manhattan jazz clubs.

After a stint in the Army, he resumed his classes at the Mannes School of Music and the New School for Social Research in New York, where he was mentored by French composer Darius Milhaud.

He also began working as an accompanist to singer Vic Damone, who fired him for allegedly upstaging him by flirting with women in the audience; to singer Paula Stewart (whom he married despite her mother’s advice that he was “really not marriage material”); and to Marlene Dietrich, the German-born Hollywood entertainer who was 30 years his senior and doted on him in a distinctly unmotherly way.

He met David in 1956 when both were working in the Brill Building, New York’s famed songwriting factory. They joined forces after a misfire by the composer and David’s older brother, Mack — a goofy title song for the 1958 B-movie “The Blob” starring Steve McQueen.

The first few Hal David-Burt Bacharach collaborations included “Magic Moments” and “The Story of My Life,” smash hits for singers Perry Como and Marty Robbins, respectively, in 1957.

Mr. Bacharach described meeting songwriter and producer Jerry Leiber, a Brill Building stalwart, as a seminal moment in his growth as a tunesmith. Like Leiber (and his partner Mike Stoller), Mr. Bacharach found an outlet for greater emotional scope when writing for R&B entertainers. He provided Jerry Butler with “Make It Easy On Yourself” and “Baby It’s You” for the Shirelles.

“You start working with non-White singers and it’s a different tone, there’s a soulful thing about it,” he told the Daily Telegraph. “And that influences what I’m composing and the way I’m working.”

The composer compared his relationship with David to an unlikely marriage — with Mr. Bacharach the cosmopolitan sybarite to his partner’s committed family man. A serial romancer, Mr. Bacharach was married four times — including once to the glamorous actress Angie Dickinson.

The composer’s dark good looks and taste in clothes put him in a vaunted social orbit. He was “the only songwriter who didn’t look like a dentist,” lyricist Sammy Cahn once observed.

His aggressive pursuit of celebrity — including the hiring of a publicist, as well as appearances in a vermouth commercial and on TV specials — reportedly gnawed at David. With playwright Neil Simon, they helped create the musical “Promises, Promises,” which ran on Broadway from 1968 to 1972.

Neil Simon, Broadway’s long-reigning king of comedy, dies at 91

© Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

Mr. Bacharach reacts to applause after receiving the 2012 Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song from President Barack Obama.

The songwriters split bitterly the next year after working on “Lost Horizon,” a musical remake of the Frank Capra-directed classic about Shangri-La. The duo reportedly clashed over the division of anticipated profits, but the movie was a legendary commercial fiasco.

Around the same time, Mr. Bacharach became mired in a legal dispute over an album he was producing for Warwick, rupturing that relationship as well.

His 2013 memoir “Anyone Who Had a Heart,” a title borrowed from one of his hits, revealed his shortcomings as a husband and father. An admittedly “selfish” man much of his life, he invited his ex-wives — Stewart, Dickinson and Sager — to contribute to provide their perspective.

In 1993, he wed Jane Hansen, a former ski instructor. In addition to his wife, survivors include their two children, Oliver and Raleigh; and a son from Sager, Cristopher. A daughter from his second marriage, Nikki, died by suicide in 2007.

Mr. Bacharach, who received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2008, expressed the deepest parts of himself in his music, which he continued to perform through recent years. Even as his voice thinned, he felt impelled to connect with an audience, to be plugged into life.

“I’m not a good New Year’s Eve act, you know what I mean?” he told the Daily Telegraph. “It’s about being able to have contact playing this kind of music. The pain that people go through — or the boredom, or the broken relationships, or the illnesses — music can be a powerful antidote sometimes. And you don’t get to see that just sitting in a room writing by yourself.”