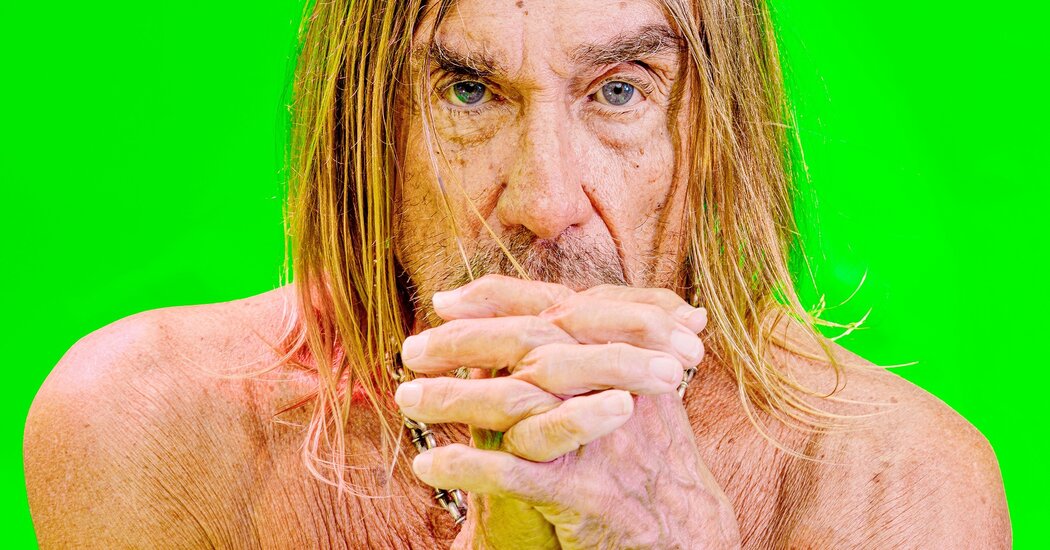

Iggy Pop’s life and work constitute one of music’s most remarkable survival stories. The savage and hair-raising ruckus he made with the Stooges in the late 1960s and early ’70s was some of the greatest and most influential rock ’n’ roll ever, and it was basically ignored or derided by the mainstream during the band’s brief original existence. Pop’s solo work has been almost as artistically significant — and somewhat more commercially successful — with albums like “The Idiot” (1977) and “New Values” (1979) continually finding eager listeners among successive waves of young musicians. Still, he didn’t really get his due until middle age, occasioned by the cultural ascension of those artists he influenced and the Stooges reforming in 2003. But his musical perseverance is only half the tale. The other half is that he lived long enough to reach beloved elder-statesman status. Pop is infamously uninhibited as a live performer — tales of self-mutilation and physical abandon are legion — and as a person (also legion are tales of substance abuse). It’s neither glib nor callous to say an early death probably wouldn’t have shocked those who knew him. Yet here he is, with 75 years behind him and a strong new album, this month’s “Every Loser,” ahead. “When I started, the demand was very low,” Pop says with a conspiratorial smile. “Now I’ve got more than enough to do.”

I think a big part of why your music still radiates, especially the Stooges’, is that its feelings of danger and transgression don’t fade. You can’t listen to that stuff and think it was made by choirboys. But my question — and it’s more general rather than specific to you — is whether an artist needs to live outside the boundaries of polite society in order to make music that also exists outside those boundaries. I don’t think it’s necessary. It’s just that if you’re living in a different way, different situations are going to present themselves. I did hang and do drugs with some tough boys. I remember when cocaine came in the Detroit area — started coming in big, probably with the biker gangs — and I did some at a party where everybody was doing it and the music was loud and the drink was flowing and an inner voice said to me, “Jim, this isn’t what you do well.” It didn’t stop me, because I heard that other voice too. But I’ve been going to bed early for years now.

Iggy and the Stooges around 1969 — from left, Scott Asheton, Ron Asheton, Dave Alexander and Iggy Pop.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Is it interesting that the voice in your head said “Jim” and not “Iggy”? Because my understanding is that for a long time there was a Jekyll-and-Hyde relationship between Iggy Pop the persona and Jim Osterberg the real person. But to my ears, anyway, the space between the two seems to have collapsed as time has gone by. The music on “Avenue B” or “Préliminaires” sounds much less attached to a preconceived persona and much more like a guy singing about his life. Is that how it feels to you? I went on that Iggy path with the Stooges, and once you start and you get somewhere, you just go with it. But what happens is, if you do that over and over, it peters out. Finally it got to a point with “Avenue B” — I was hitting 50 and hitting a wall, and I was fed up, and as I said on the first song, “I didn’t want to take any more [expletive].” If you yell, “I ain’t gonna take any [expletive]” on a rock song that’s one thing. But if you quietly say it to some sepulchral music, that’s a different thing, because you’re facing darkness once you hit 50. I was also having a divorce, so I wanted to sing about a Nazi girlfriend and trying to [expletive] her on the floor. It was a dark feeling. But I always believed that if I did it — whatever it was — for real, then an audience was going to be there. And “Préliminaires” came about because I was at an age where Michel Houellebecq’s novels were important to me. There are some very comic, soulful and sensible solutions to middle-aged male problems in those novels. I was asked to contribute a song to a documentary about him, and then other songs on “Préliminaires” were triggered by Michel’s books. The point of all this is, if you keep going, possibilities open up.

Michel Houellebecq is a writer a lot of people disagree on. Yeah, I can never understand why. But that shows who I am.

Maybe it does. But one subject that makes people take issue with him is the way he writes about sexual power dynamics. Whether he’s accurate or not, who knows, but he’s opening a window on certain ways of thinking. And hearing you mention him makes me wonder if you can do that, too, because it’s clear from reading books about you that back in the ’70s you were pretty much living the stereotype of the sexual-free-for-all rock ’n’ roll lifestyle. How do you think about that experience now, when attitudes about sex have shifted so much? I’m even thinking of your own memoir, in which you were talking about a 13-year-old, and you said, “She looked at me penetratingly” and then “You can figure out what happened next.” Well, now I’m married to someone around 50 years old and I’m a much different person than I was.

I know you are, and I’m not judging or asking you to judge. But I’m asking if you can recall how you understood the sexual dynamics of the rock-music world back then. Maybe you had ambivalence, maybe everything seemed great, maybe you just didn’t think about any of this at all. I don’t have much to tell you. I’m not going to list in detail my experiences when they’re that private, other than in terms of what you read.

Pop performing in Cincinnati in 1970.

Tom Copi/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

I’m definitely not asking you to detail private experiences. I’m asking about feelings and thoughts. I don’t think that I was really thinking about anything. Except I think most artists, when they’re young, pursue beauty when it presents itself. Things were much different in those times in general. Much, much different. That’s all I would say about that.

Ah, OK. The new album is kind of more meat-and-potatoes rock ’n’ roll than your last few. Why did you go back in that direction? It was Andrew Watt. We talked because he wanted me to work on a Morrissey record. I was speaking with Andrew, and after a half-hour on the phone, he says to me, “Are you ready to be yourself again?” I said, “Which one?” because I didn’t want to get nailed down by this kid. But I knew what he meant. I said, “Sure, send me some tracks.” As the tracks came, I saw the opportunity. For some time now, my M.O. has been like a chick at the disco, you know? You dress up, go sit by the wall, and see who asks. That’s pretty much it.

On the credits of the new album, you give special thanks to Taylor Hawkins. He’s not the only guy you made music with whom you lost prematurely. Do you ever wonder why them and not you? Is there a way you’ve tried to make sense of it? My doctor tells me I have a strong immune system, but I don’t think that’ll do it for you. By some miracle, at certain times I pulled back. The other thing — it’s hokey maybe, but maybe not — is my mother’s love and prayers. I believe that. Because there were times when it just — there was one time I was hanging out with a couple members of the MC5 and I turned blue. They didn’t know what to do. I just remember I woke up in a bathtub full of ice. They threw me in ice, and that didn’t work, so they shot me up with salt to bring me back. There were a couple of different times. Not just with that but also with drug-related boom-boom.

Pop in 1970.

Tom Copi/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

What do you mean? Once, in Hollywood, the hotel that is now the Mondrian used to be a pretty edgy condo building, and I was in the same room with somebody who had a large vial of cocaine, and it turned out to be stolen. There was a knock on the door and the lady whose apartment it was opened the door a little and boom! A big guy burst in, and then a bunch of guys behind him all with guns. They put guns to everybody’s head, and while they were trying to figure out what to do with us, one of them said: “That’s Iggy! Let him go.” [Laughs.] Now, that’s just — whoa. That moment is one for which I’m eternally grateful.

And you believe your mom was looking out for you at times like that? Hovering over me. She never gave up on me. She would send me an envelope about once a week when I lived in Los Angeles with a $20 and a $5 in it. I could always talk to her on the phone. But there were dangerous times. Another time my arms swelled up because of poison in my system. Once I started seeing a doctor regularly, the doctor said, “Well, you’ve certainly done some drugs.” Then he said, “You had an infected heart, and you have healed.” He also told me it’s enlarged by about 50 percent — muscle-bound, because it had to work so hard. I think about these things sometimes and try to make life worthwhile, try to enjoy something. Not everything. [Laughs.] Try to enjoy when you can be a good guy. Other than that, I don’t know. It was 1983 when I made a conscious decision: I have to stop the way I’m living. I have to clean up. I have to be with one person. I went that way, and for about a year I’d trip every month or two and make a big mess, but then it stuck.

What made you change? I could see the end of the road. My teeth were falling out, my ankles were swelling up, my music was getting [expletive]. I wasn’t satisfying myself or doing good for anybody else.

Pop around 1979.

Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images

You said your mother never gave up on you. Did you ever give up on yourself? Not consciously. There was a certain period when I had a mixture of frustration and it turned to anger, and as it turned to anger, the anger — once you give in to that then you’re not yourself anymore. Just like you’ve got to work on your music, you’ve got to work on yourself too. I don’t get a gold medal for anything, but I never gave up on making art. Never gave up that — one bit.

The other day I saw that an old Patti Smith song with a racial slur in the title was taken off the streaming services. And then I was listening to the “New Values” album and heard your song “African Man,” which doesn’t have anything nearly as bad as that slur in it but the joke of it sure hasn’t aged well. It made me wonder what you think about the idea of taking offensive material out of circulation. “African Man,” here’s what happened: I nicked a lyric, and I didn’t even mean to. I couldn’t think up anything else to go with that music, and I had seen an African artist play in a tiny club in Berlin, and it was totally different music. But he had that lyric, and I thought, Boy, that’s fun, and why can’t I sing that too? Right away, a lot of people, people like you, people who do the job of thinking and commenting, critics, said what a terrible song this is. I would put it this way: It’s the weakest song on the album. If the record company wanted to knock that off the album, I’d be all for that.

But my question is not about that one song so much as it’s about the bigger question of expunging material after the fact. I mean, I bet there’s also material on “Metallic K.O.” that maybe you aren’t thrilled about. But that’s also a historically important record the way it is. You mean would I try to suppress that? No. I would say that’s an individual decision and depends on the type of artist and person you are. I can’t see what possible value — OK, nobody would ever hear me say, “You throw all this [expletive] you want at me, your girlfriend’s still gonna want to blankety blank blank!” Big deal. We did a gig, it wasn’t going very well, and some guy thought, This is an interesting document, I’m going to put it out. At least it was different than the same old contrived [expletive]. If I decided I was going to go now and try to clean up everything I’ve ever done, that would make me Sisyphus. I’d be rolling that damn stone up the mountain until I die.

Pop during a performance in 1993.

Catherine McGann/Getty Images

Whenever I watch old concert footage of you or look at old photos and see the way you were using your body — it’s this tool for confrontation. But these days, at least the times I’ve seen you play, your body evokes totally different feelings — joy and even solidarity. When did you realize your body meant something different than it used to? It came on as people first seemed to be accepting the music. Then I started noticing they were accepting me. That’s an awfully good feeling, especially after you’ve been at it for 50 years. I’m nicked up at this point. I broke a foot. I dislocated a shoulder. There’s osteoarthritis in the right hip and the body in general. There’s scoliosis in the spine. But I can center a song better than I ever could. I know what I’m doing. Since the Stooges re-formed I’ve had nothing but good bands. I don’t have to get drunk and stoned to make the music sound good. I did that for many years. But in 50 years maybe I did two bad shows. I remember one was at the Ritz in New York City. It was probably around 1980, ’81. I was feeling like I don’t have the energy for this tonight, and the bass player said, “I’ve got a hit of orange sunshine.” So I took a hit and — woo! I walked out on stage and the band started the first number. I looked to my left and I looked to the right and I waved my hands and said: “Stop! That sounds like [expletive]! Play something else!” I tried to walk offstage and my tour manager grabbed me and said — he’s Scottish — “Ye are going to stay on that stage for 45 more minutes or we’re not getting paid!” and he pushed me back out. I think that night I broke a Jack Daniel’s bottle over the microphone. It was a mess. I got cut up a little. But I’ve done good work when it comes to the gig. That’s always been the one place where I felt, OK, whatever you take away from me, I can control that. I don’t how I started on that rant, but you got me going!

That Scottish manager you mentioned before, was that Tarquin Gotch? No, no. Tarquin was at one of the record companies I was at for a while, wasn’t he? I’m talking about a guy named Henry.

I was curious because I thought Tarquin Gotch was involved in your career at some point and now he’s involved with AC/DC, which is a whole other side of the hard-rock coin. Actually, what’s his name, Scott, the AC/DC singer?

Bon Scott. Yeah, Bon. I had some very wonderful encounter with Bon somewhere, and we were both drunk and stoned. I see pictures sometimes. I go, I don’t remember, but that’s me with Bon! I loved what he did. They had a manager many years ago, when I hadn’t re-formed the Stooges, I hadn’t moved to England, and this guy said, “Are you interested in joining AC/DC?” They were looking for a singer.

Whoa, that’s a real what-if scenario. Did you consider it? No, because I listened to their record. I thought, I can’t fill that bill. I wasn’t like, ugh, I don’t like them. It was quite well made. They do careful work. But I’m not what they needed.

Pop performing in New York City in 2009.

Michael Loccisano/Getty Images

You said before that it wasn’t until relatively late in your career when you started to feel that audiences accepted you as a person. So back in like — I’m just throwing out years here — 1975 or 1983, what feeling were you getting from audiences who came to see you if it wasn’t acceptance? They were just kind of staring at me. In the era from ’75 to ’83 pretty much everybody just stared at me. All over the world, people stared.

You felt like a curiosity? I’m not sure. I was never sure what it was. I thought, Better this than not getting attention. But still, I wanted something more.

How much is your overall view of humanity and your own internal sense of worth dictated by the external response to your music? One hundred ten percent. I’ve been thinking, What is it about “Metallic K.O.”? And I remembered, Oh, [expletive], that’s got “Rich Bitch” on it. I was very angry and hurt, and I had somebody in mind, and I wasn’t doing well in my career, and I thought that person was the reason I wasn’t. So yeah, I went through negative stages until finally that got better by degrees and I wasn’t giving up on audiences or lashing out.

So now, when the career vibes are all good, it’s fair to say that you feel better about other people and the world? You betcha. [Laughs.] I’ve got to say, it makes all the difference.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations.

David Marchese is a staff writer for the magazine and writes the Talk column. He recently interviewed Lynda Barry about the value of childlike thinking, Father Mike Schmitz about religious belief and Jerrod Carmichael on comedy and honesty.