The musical tastes of King Charles III are more sophisticated than those of our late Queen. That’s not being rude: it’s just a fact. Her favourite musician appears to have been George Formby, whose chirpy songs she knew by heart. No doubt she relished their double entendres – but the hint of smut meant that, to her regret, she had to decline the presidency of the George Formby Society.

Our new monarch, by contrast, adores the Piano Concerto in E flat major by Julius Benedict (1804-85). He recommended it in an interview a couple of years ago. I’d never heard of the piece, which existed only in manuscript until Howard Shelley and the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra recorded it for Hyperion in 2008. So I have our new king to thank for alerting me to this gorgeous confection – not quite a masterpiece, but full of pretty tunes connected by glittering filigree passagework that wears the poor pianist’s fingers to the bone.

I also didn’t know of the existence of Scylla et Glaucus, the only opera by Jean-Marie Leclair, an 18th-century French composer of violin sonatas. The then Prince of Wales chose a scene from it when he appeared on Michael Berkeley’s Private Passions on Radio 3 in 2010, describing it as ‘incredibly rhythmic and exciting’ and ‘one of those bits of music that put a spring in your step when you’re feeling a little bit down’.

Sometimes the guests on these programmes are bluffing about their love of highbrow music chosen for them by someone else. (I once had to come up with ‘personal favourites’ for a tin-eared guest.) But the King’s problem will have been the opposite: whittling down his most beloved pieces to a shortlist.

Charles III is the first British monarch for more than 100 years for whom classical music is a passion

He’s the first British monarch for more than 100 years for whom classical music is a passion, and not just a private one. He’s patron of the Royal College of Music, the Philharmonia Orchestra, the English Chamber Orchestra and many other bodies. None is closer to his heart than the Monteverdi Choir, founded by his friend Sir John Eliot Gardiner, a gentleman farmer with, conveniently, similar views to Charles. In 2000 Deutsche Grammophon pulled the plug on Gardiner’s cycle of Bach cantatas; he finished it by setting up his own label, SDG. The lavishness of its products is a marvel; I suspect we’ll never find out how much assistance he received from Charles.

Like any music buff, the King has obsessions. He is determined to rehabilitate Sir Hubert Parry, best known as the composer of the only sacred anthem performed by drunks at stag nights and rugby club dinners. Charles has even presented a BBC documentary pointing out that Parry, in addition to writing ‘Jerusalem’, ‘I was glad, blest pair of sirens’ and staple evensong fare, wrote marvellously for the orchestra. His later symphonies and Symphonic Variations would be better known if it were not for Elgar, a younger man born with the skills that Parry worked hard to master. But perhaps there was envy in both directions. The Old Etonian Sir Hubert, whose family seat in Gloucestershire, Highnam Court, boasts some of England’s loveliest gardens, was what Elgar desperately wanted to be: a proper country gent. Parry held surprisingly radical views, however, and beneath the conventional surfaces of his best music lies subterranean fire. Charles is his natural champion.

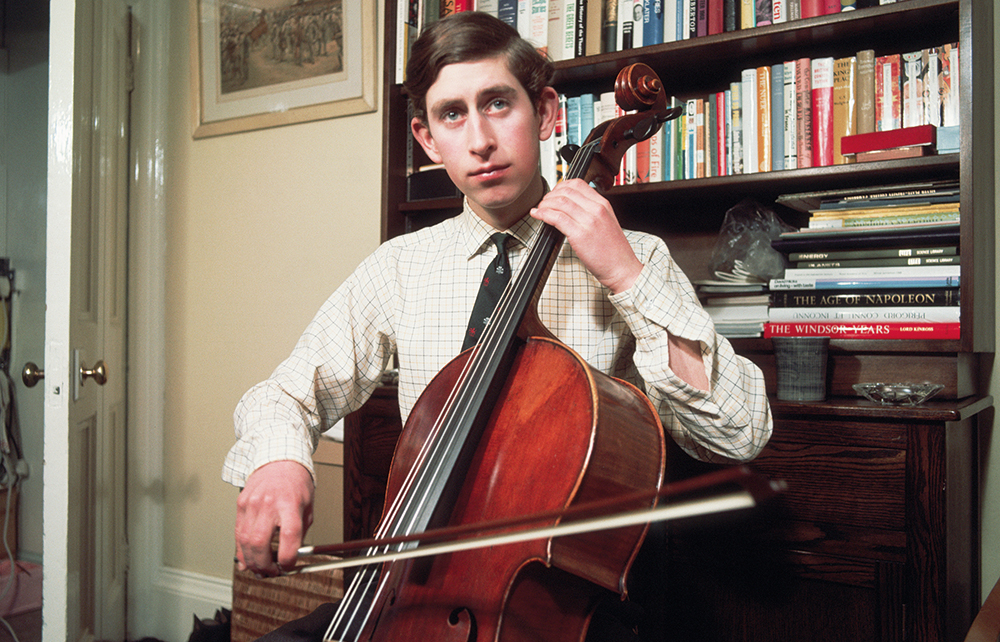

The King has listened to symphonies and operas since he was a child, when he also learned piano, trumpet and cello. I wonder if that contributed to the bullying at Gordonstoun: in many schools, boys who like classical music walk around with targets on their backs. And I doubt that it endeared him to his family. For the House of Windsor, serious music should be kept in its place: in church, and they don’t want to hear anything they don’t already like.

But if Charles’s enthusiasms are unusual in his immediate family, things look different in historical perspective. The Windsors are the anomaly. From the accession of Henry VII until the death of Edward VII, almost every English monarch was a music lover. Henry VIII was a composer; he didn’t write ‘Greensleeves’ but 33 court manuscripts are ascribed to him, brimming with talent. Ironically he was responsible for the brutality of a Reformation that devastated musical life – but it revived under Elizabeth, who practised the virginal religiously and commissioned music from William Byrd despite knowing he was a Catholic.

All the Stuart monarchs were musical. James I and Charles I presided over masques that rivalled those of the most lavish European courts. Under the later Stuarts, the Chapel Royal became a musical battleground. Protestants disliked Charles II’s fondness for instrumental music in church; James II, whose Chapel Royal was elaborately Catholic, was accused of trying to force popish music on Anglicans. The Calvinist William III intended to ban instrumental accompaniment for anthems, but the temptation to commission Henry Purcell to write for trumpets and drums proved too great. Under Queen Anne, every victory or feast day was marked by a blazing anthem. And who better to write them than George Frederick Handel, now living in England after a row with his employer in Hanover?

The late Queen’s favourite appears to have been George Formby, whose chirpy songs she knew by heart

In 1714 that employer became King George I; fences were mended and the first four Georges promoted the cult of Handel. George III organised private concerts of his music for which he wrote the programmes in his own hand. Not until Haydn visited England did a composer enjoy such celebrity. One of Haydn’s patrons was the future George IV, who employed his own orchestra and according to Haydn had ‘an extraordinary love of music’.

Victorian musical life seems drab by comparison. But never has there been a more musically obsessed royal couple than Victoria and Albert. They played Beethoven symphonies in piano duet; they accompanied each other in songs by their favourite living composer, Mendelssohn, and were thrilled to be visited by the ‘short, dark, Jewish-looking composer, delicate, with a fine intellectual forehead’, as the Queen described him. The Prince Consort and the composer shared a Lutheran faith and a love of Bach: it was thanks to Albert that the St Matthew Passion was first performed in Britain. Albert prepared the ground for the opening of the Royal College of Music by his son, the future Edward VII. ‘Bertie’ preferred the theatre, especially actresses, but he did leave an indelible mark on British musical history. He liked to hum the trio section of Elgar’s first ‘Pomp and Circumstance March’ and suggested it be set to words for his coronation. Hence ‘Land of Hope and Glory’.

Curiously, for much of this time the post of Master of the King or Queen’s Music was relatively insignificant; the holder of the office when Victoria was crowned, a nonentity called Franz Cramer, couldn’t even produce a coronation anthem – a failure described by The Spectator in 1838 as ‘a defilement of the national honour’. But for the most part it didn’t matter, because the real master of the royal music was the monarch.

The composer Sir James MacMillan, who wrote an anthem for the Queen’s funeral, says our new King has ‘an intense and knowledgable love of music, and his influence has already been felt in some of the liturgies we’ve seen in recent years’. That’s worth noting, given that even under the most difficult circumstances, such as the Duke of Edinburgh’s funeral during the pandemic, the music has been breathtaking. King Charles has promised not to interfere in politics, but music is another matter. So in that respect this reign will be interesting. Or, as MacMillan puts it, ‘very fruitful for music’.