Legends of Hindustani classical abound at Dover Lane Music Conference

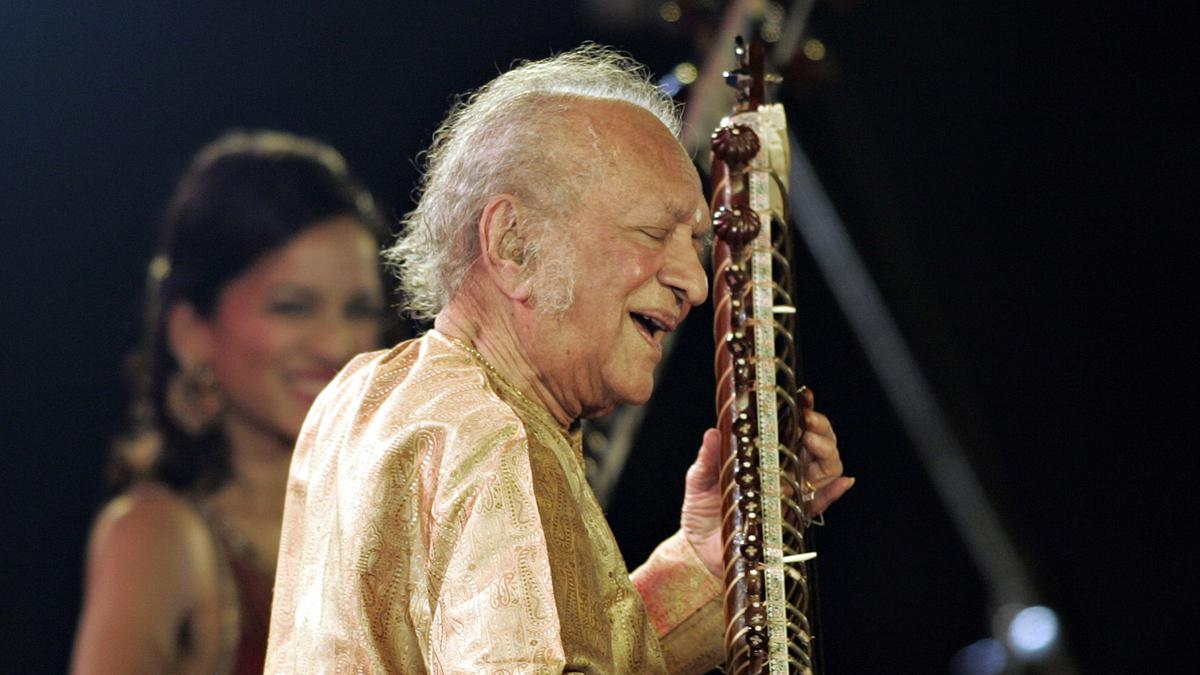

Pandit Ravi Shankar (R) and his daughter, Anoushka Shankar (L, background), perform at Dover Lane Music Conference in 2009.

| Photo Credit: DESHAKALYAN CHOWDHURY

It is the experience of hearing and watching them live all through the night that draws audiences.

In the early hours of January 27, 1986, as sitar legend Nikhil Banerjee played at the all-night Dover Lane Music Conference in south Kolkata, he started feeling uneasy. Forced to cut short his performance, he played one last piece—raga Deepak—at the audience’s request before taking his leave. It was one of the most sublime renditions of the raga, said Monotosh Mukherjee, one of the organisers of the annual music festival who was present at that time. “It was out of the world. The audience was mesmerised.” Hours later, Nikhil Banerjee passed away. He was 54.

Such stories about legends of Indian classical music are inextricably linked with Kolkata’s iconic Dover Lane Music Conference, which turned 70 in 2022. Over the years, it has been the venue of not only some of the most memorable performances by maestros but has also launched new stars who have gone on to make a name for themselves.

How it began

But the beginnings were anything but portentous: the concert started off as a result of a friendly rivalry between two adjacent localities in south Kolkata. “It was essentially a para (neighbourhood) function that started in 1952, meant to counter a neighbouring event. Even those who began it never thought that it would get so big eventually. Initially, it was more of an all-round entertainment event where, along with music, there were plays, dance recitals, and other performances,”said Bappa Sen, governing body member and former general secretary of the Dover Lane Music Conference. Playback singers such as Shyamal Mitra, Manabendra Mukhopadhyay, Sandhya Roy, who were big names in the Bengali film industry, performed here. Then sometime in the late 1950s, the programme shifted its focus from popular music to classical.

In the late1960s, however, internal issues in the organisation and the violent Naxal movement forced Dover Lane to go into a decade-long hiatus. It was not until 1978 that it was revived, and since then it has been held uninterrupted (even during the COVID-19 pandemic) every January. Under the leadership of a group of committed organisers, including Dipamoy (Rotu) Sen, Bula Ghosh, Saroj Dasgupta, and Ajit Ghosh, the Dover Lane concert moved from strength to strength. “It is because of their efforts that Dover Lane Music Conference is what it is today. They showed us the ropes, and we in turn have passed on their lessons and values to the ones who came after us,” Sen said.

“It was not uncommon to see one legend coming not to play but to listen to another.”

Over the years, the biggest names in Hindustani classical music have played at Dover Lane, including Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Dattatreya Vishnu Paluskar, Ustad Amir Khan, Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Bismillah Khan, Nissar Hussain Khan, Bhimsen Joshi, Gangubai Hangal, and Hirabai Barodekar, besides maestros from Pakistan such as Ustad Salamat and Nazakat Ali Khan. The concerts have not just been about the performances: they have offered an intimate insight into the personalities, idiosyncrasies, passion, and genius of the legends. There is always an element of drama when the stalwarts perform, and it is this overall experience of hearing and watching them all through the night until the cold wintry dawn that has made the audience come back year after year for seven decades.

| Photo Credit: PTI

Everyone who has ever attended a Dover Lane Conference has some anecdote to narrate, such as during a performance of Pt Ravi Shankar and Ustad Zakir Hussain, the sitar legend stopped playing to listen to the young tabla maestro, son of his former jugalbandi partner Alla Rakha, enthralled by Hussain’s strokes on the tabla as he continued solo for a few minutes. The applause at the end was tumultuous.

On another occasion, Bhimsen Joshi was so immersed in his singing that he did not realise he had turned his back to the audience. Upon opening his eyes, the master saw the curtains at the back of the stage and demanded that they be removed so that he could see his listeners. Snigdha Sen, who attended the conference quite regularly between 1960 and the late 1980s, remembers the time when Nissar Hussain Khan fell ill on stage while singing. “He suddenly stopped. But when they tried to take him back to the green room, he refused. He insisted on singing. While it was painful to see him in discomfort, we also got an inkling of the commitment and passion he had for his art,” Snigdha told Frontline.

At the time Dover Lane was revived in the late 1970s, classical music was on the wane in Kolkata. “Popular music was the craze at that time. Other organisations that used to host programmes of Hindustani classical music were shutting down, and there was a vacuum that Dover Lane filled when it restarted,” said Monotosh Mukherjee.

| Photo Credit: Special arrangement

Speaking of her experience of attending the concerts, journalist Indrani Dutta said: “It was an immersive experience. I used to attend the all-night sessions, come home, go to office, and then go back again for the next concert that very evening. In the wee hours of the morning as the concert ended, I would leave with the strains of music in my head which would continue to reverberate long into the day.” She recalled that once she was so moved by a particular performance that she surreptitiously made a recording. “I have always been a compliant person who follows the rules. But on one occasion, the artiste was so good that I could not help recording on the sly the last bit of the recital,” she said.

Snigdha said that as a student of music at that time she was amazed to see all those musicians together. She added: “Some performances still resonate—listening to Amjad Ali perform with Hariprasad Chaurasia at the crack of dawn, we were transported to a different world.” Snigdha, who has trained under such legendary singers as Sukhendu Goswami and Satyakinkar Bandopadhyay, would sometimes attend Dover Lane with fellow students. “Often, after the concert, my friends would accompany me home and practise what we had heard over the night,” she said.

The old-timers remember the 1980s as a bygone era when music and culture were different from what they are now. Bappa Sen recalled that during the 1983 edition, Bhimsen Joshi suddenly called to say that he would not be able to perform that evening as he was unwell. The organisers had to find a suitable replacement on short notice. “We requested Pt Manas Chakraborty and practically picked him up from his residence. Manas da gave a spellbinding performance,” said Sen. “There was a lot less ego in the great artistes of yesteryears,” said Sen.

A different era

On another occasion, the organisers desperately needed a replacement for a celebrated artiste who had cancelled his performance at the last minute. “There were only landlines in those days, but we managed to track down Hariprasad Chaurasia ji at a hotel in Ahmedabad. He was returning to Mumbai after a concert. The then general secretary of Dover Lane requested him to come to Kolkata instead that evening, and Chaurasia ji immediately agreed. He came, played, and left,” said Bappa.

It was not uncommon to see one legend coming not to play but to listen to another. “Once Pt Ravi Shankar had come to the conference just to hear Ali Akbar Khan’s recital. He was not playing that year. Once Pt Jasraj, who had come to perform, was on his way from the airport to his place of stay. While going past the concert venue, he heard Chhannulal Mishra singing. He got out of the car and came in. The situation has changed a lot in every way, but it is best not to dwell on such things,” Bappa added. The ambience of the venue has changed too. Until about 10 years ago, all the concerts—whether in Dover Lane (until 1982) or Hindustan Park (until 1985) or Vivekananda Park (until 1990) or Nazrul Mancha (to date)—used to take place in the open air. This lent a peculiar characteristic to the event as in the cold winter nights and early mornings, the artistes would often find their instruments going out of tune and retune in between recitals.

Once sitar legend Vilayat Khan was retuning his instrument in the early hours of the morning when a section of the audience thought that the performance was over and started leaving. The maestro put down his sitar and said: “Those of you who wish to leave please go ahead. Those who want to hear me continue playing may remain seated. I will start once everybody who is leaving has left.” The confused, embarrassed, and delighted audience at once scurried back to their seats to hear the rest of the concert. Such confusion is not likely to happen any more as Nazrul Mancha, once known as the Open-air Theatre, has now been converted to a covered auditorium space.

With changing times, Dover Lane has also branched out. One of its most important functions is to promote the younger generation of classical musicians and singers, who are given a chance to perform alongside the legends. Abhijit Majumder, current general secretary of the organisation, refutes the claim that the younger generation is not of the same calibre as the older artistes. He said: “Many say that Amaan Ali Khan does not play as well as his father, Amjad Ali Khan. Of course, he doesn’t since Amaan is just starting out. At his age, Amaan is playing very well, and if we do not listen to him now, how will he become an ustad later.”

| Photo Credit: Dover Lane Music Conference

Dover Lane has reportedly “discovered” new singers through talent search contests. “Arijit Singh claims that he was discovered by our organisation. Famous classical singer of the Kirana Gharana, Sohini Roy Chowdhury, and the popular sarod sisters, Troilee and Moisilee Dutta, have all been associated with us,” said Majumder. But the organisers do feel there is a decline of interest in classical music. “Many think that it is a status symbol to be seen at Dover Lane. People get the tickets, we expect a houseful, but on the day of the show, the auditorium is only half filled. Earlier we had people sitting out in the cold listening to the music inside,” said Majumder.

However, for genuine lovers of Hindustani classical music, Dover Lane is one of the most important events of the year. Artistes are aware of that; during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the auditorium could only accommodate 50 per cent, many musicians either performed free or took a token amount. Performing at Dover Lane is still considered an honour, even if its glory has dimmed somewhat over the last few years.

The Crux

- Stories about legends of Indian classical music are inextricably linked with Kolkata’s iconic Dover Lane Music Conference, which turned 70 in 2022.

- The concert started off as a result of a friendly rivalry between two adjacent localities in south Kolkata.

- Over the years, the biggest names in Hindustani classical music have played at Dover Lane.

- The old-timers remember the 1980s as a bygone era when music and culture were different from what they are now.

- With changing times, Dover Lane has also branched out. One of its most important functions is to promote the younger generation of classical musicians and singers, who are given a chance to perform alongside the legends.