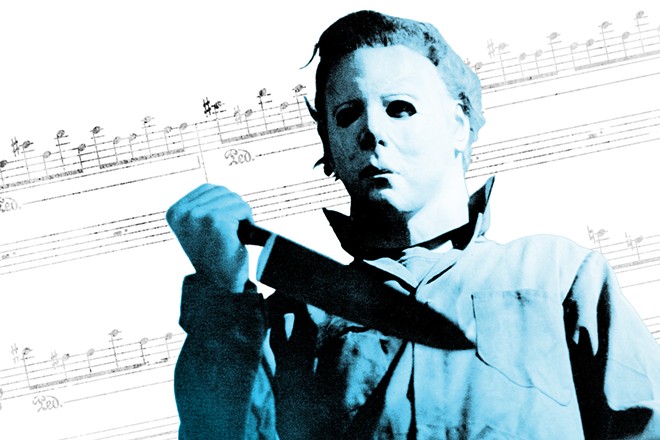

Michael Meyers wouldn’t be the same without John Carpenter’s iconic, bone-chilling score.

Earlier this year in the pages of the Inlander, I wrote about how so-called “elevated” horror films had begun to stake their claim in the summer blockbuster landscape. But now that spooky season is in full swing, thrillers, slashers, monster flicks and their ilk have crawled out of their coffins to dominate pop culture for a month. One crucial element for any effective horror movie — quite possibly to a more pronounced degree than with any other cinematic genre — is an impactful score. The best of the best stick to the viewer like so many gallons of Kensington Gore (aka fake blood) long after an initial watch. So it felt like a perfect time to explore some of the most iconic horror soundtracks of all time, along with some underrated gems.

Let’s get the classics out of the way first. Sometimes, the strength of a score lies with the simplicity of its leitmotif — melodies so iconic that they transcend the films themselves and become tattooed on the universal psyche. Take, for example, the brilliant economic two-note pulsing dread of John Williams’ Jaws score or the shrieking violins of Bernard Herrmann’s strings-only score to 1960’s Psycho, which perfectly syncs with the visuals of the overkill stabbing of Janet Leigh during the infamous shower sequence.

When polymath horror legend John Carpenter first sat down at his synthesizer in the late 1970s to compose the haunting, repetitive score for his foundational slasher movie Halloween, the music’s lack of ostentation was borne out of his limited means as a scrappy independent filmmaker as much as it was creative intentionality. What he landed on was a barebones 5/4 melody that his father had taught him as a child, which now will be forever synonymous with late night heebie-jeebies. This month, Carpenter revists the unforgettable score via the recently released Halloween Ends, which supposedly serves as a capper to the long-running franchise (it’s proven to be as unkillable as the bogeyman himself, Michael Myers).

The brilliant horror scores of the ’70s don’t end there, however. At the outset of the decade, famed composer Ennio Morricone made the genius decision to contrast the sexualized violence depicted on screen in Dario Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (a hallmark entry in the Italian giallo horror subgenre) with an unexpectedly beautiful, innocent-sounding theme. A Nightmare on Elm Street and every other subsequent horror movie that weaponized childlike sing-song falsettos owes the late maestro a debt.

“When I think of the scores that scare me the most, they’re the ones with creepy kids singing,” says Colleen O’Holleran, who programs the “WTF” series (Weird, Terrifying, Fantastic) for the Seattle International Film Festival.

Later in the ’70s, Argento would recruit the prog rock outfit Goblin (with whom he’d previously collaborated on another celebrated giallo film, Deep Red) for the soundtrack to his lush, witchy Suspiria. It’s a score that’s at times whimsical, at times discordant, and splashed throughout with warbling synths.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre boasts an equally idiosyncratic score composed by its writer/director Tobe Hooper and Wayne Bell. Hardly musical at all, it’s an experimental, macabre collage of sound effects, ambient noise, and grating drones of musique concrète (music composed using the sounds of raw material).

Special mention must also be paid to the spine-tingling “ch ch ch ah ah ah” of the Friday the 13th franchise, which was so indelible that I (and one can only presume many others) were taunted with it on childhood playgrounds. Apparently, the iconic noise resulted from composer Harry Manfredini sublimating the phrase “Kill her mommy” (as uttered by Pamela Vorhees, the killer of the first film in the franchise) into its most rudimentary syllabic form.

Jumping ahead in time and offering a refined contrast, Candyman (1992) exists on the more cosmopolitan side of the horror landscape with a score by wildly influential and adored composer Philip Glass. (Though when asked about the music for Candyman, Glass’ tone is usually dismissive, unbefitting of his masterful amalgamation of elegiac pianos, booming choirs and cascading pipe organs.)

More recent efforts within the genre also deserve their moment to shine under the moonlight. In 2018, director Luca Guadagnino released a controversial remake of Suspiria, one which altered the setting and themes of the original and bleached out all of Argento’s signature vibrancy. To accompany this radical and more muted reinterpretation, Guadagnino’s film required a drastically different sonic palette to accompany it. To take on this challenge, the director roped in Thom Yorke of Radiohead. Yorke’s Suspiria score is subdued instead of splashy, and redolent with the kind of minimalist melancholy that characterizes many of his solo outputs.

On the other end of the aural spectrum lurks Cliff Martinez’s score for 2016’s vicious, opulent fashion industry satire, The Neon Demon. Like his previous collaborations with divisive Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive‘s soundtrack ranked No. 19 on Pitchfork‘s list of “The 50 Best Film Scores of All Time”), the critically acclaimed score is heavy on atmospheric synth tones, but features an additional injection of throbbing club music rhythms; it wears its electronic musical influences proudly on its haute couture sleeve. Fascinatingly, Refn had cut The Neon Demon to a temp score of compositions by Psycho composer Herrmann, but Martinez wisely disregarded this completely and followed his own impulses to great effect.

There are far too many quality horror scores to give them all proper recognition, to say nothing of the great horror needle-drop soundtracks. You will never hear “Hip to be Square” or “Blue Moon” the same again after watching American Psycho and the lycanthrope transformation scene in An American Werewolf in London.

Clearly, there are a lot of directions a composer can (and should!) take when scoring a horror film. The very best stand out from the rest of the (were)wolf pack because of their innovation, their ability to make the most of the sometimes-limited resources at their disposal and their willingness to take risks. Others help ground the viewer in a character’s perspective, be they the archetypal final girl or the antagonist stalking the film’s frames.

As O’Holleran puts it, “In terms of memorable horror movie scores, they work best when they subconsciously connect you to the character.”

The beautiful thing about the horror genre is how it can be adapted in wildly divergent ways. Don’t be afraid to have your Halloween party playlist reflect this diversity.