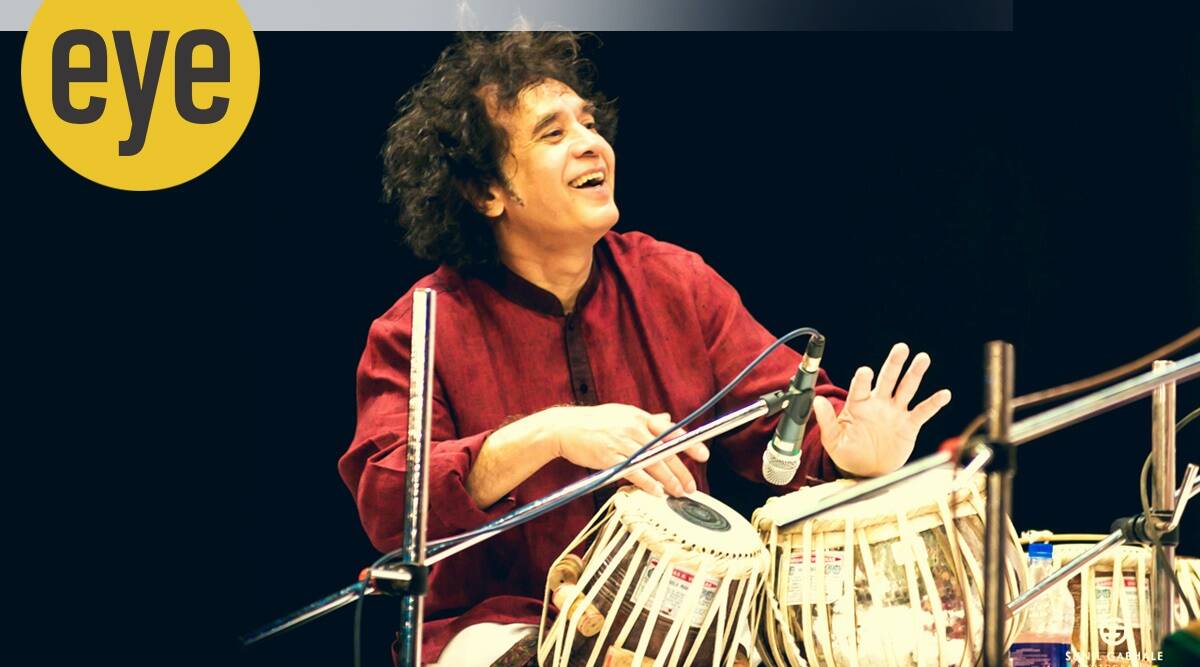

Just after ace percussionist Ustad Zakir Hussain, one of the tallest names in the world of rhythm, drummed up a storm with an intricate rhythm pattern that landed exquisitely on the sam (the first beat of the time cycle in a rhythm structure) at Delhi’s Siri Fort auditorium earlier this week, an elderly man in the audience exclaimed, “Uff ye ladka, kya tabla bajaata hai (How brilliantly does this boy play the tabla)!”

Hussain, 72, was accompanying Delhi-based sarod exponent Ustad Amjad Ali Khan in a concert organised by Mumbai-based organisation Pancham Nishad. What the overtly enthusiastic gentleman and the audience could not spot, however, was that amid a flurry of virtuosic rhythms and broad smiles, Hussain has been dealing with anxiety and apprehension since his arrival at his parents’ Nepean Sea Road home in Mumbai earlier this month.

Every year, the visit to India in winter is what Hussain really looks forward to. Here, he gets to deep dive into his core — Hindustani classical music — and discover “what new things one has accumulated in the time that’s passed”. But this year is replete with a sense of loss and longing for two of his closest associates — santoor maestro Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma and Kathak exponent Pandit Birju Maharaj, who passed away earlier this year.

“These are relationships that have shaped my life, me as a musician, showed me which path to take. To not see them around does not feel right. It’s almost as difficult as me trying to get on stage in India for the first time after my father passed away, because these are mentors I grew up learning from. It feels as if a major part of me as a listener, as a student, as a nurturer, a preserver and transmitter of music, has fallen away, and I don’t know how that’s going to come back. That makes me extremely anxious,” says Hussain in an exclusive conversation with The Indian Express over a call a few hours after his arrival from San Francisco, California, his home with wife and Kathak dancer Antonia Minnecola.

The poignant moment when he played pallbearer for Sharma’s hearse in May this year, his grief palpable, was discussed extensively on social media as the true example of the “idea of India”. For Hussain, it was not as reductive in nature, but only a gesture to mark the deep bond, musical and otherwise, the two had shared over the years. “I think people and politicians exist on two different planes… We tend to generalise and in doing so, create the danger of a bigger schism than we actually need to. Not everyone of any sect is bad. That idea seems to have taken a backseat. What we need to do is just be able to hear whatever the powers that be want to tell us, but judge for ourselves as citizens where is it that we belong and what it is that we need in our lives to make it better. Probably we’ll get there one of these days,” he says.

As much as one considers his concerts in India an easy home stretch, Hussain believes that the last three years, riddled with uncertainty, death, loss and loneliness, have left him flailing to figure out the audience’s pulse. “I don’t know what they like anymore after listening to so many Zoom concerts and seminars,” says Hussain. He need not have worried. Going by his sold-out tour this time, Hussain appears to remain peerless in the world of Indian percussionists.

During the Delhi concert, the deft sonic artiste enthralled the audience without ever overpowering the performance, in which, traditionally speaking, Khan was the main artiste. His solo, like the one today in Mumbai’s Thane, organised by A Field Productions, is a different ballgame. It’s an ode to the gurus who have taught him, a hazri (attendance) in the court of music. “The story of Thane goes back 60 years, when, as a young boy studying in Class V at Mahim’s St Michael’s, I was made a part of a variety show in a dark, small hamlet that Thane was once, alongside bhangra performers, mimicry artistes, film singers. This is the first time I felt that I belonged,” says Hussain, who learned under the exacting tutelage of his father and guru, Ustad Allah Rakha.

With a rich classical career behind him, this year also marks 50 years of Shakti, one of the finest world-music bands, which began as a collaboration between Hussain, British musician John McLaughlin, US-based violinist L Shankar and ghatam legend Vikku Vinayakram. The group merged Indian music with jazz, creating a unique sound. While the audience fell in love, the jazz world was less forthcoming. Unlike Pandit Ravi Shankar, who had pop’s biggest name, George Harrison, rooting for him, Shakti was an experiment that took time to make its mark. “Away from the Indian classical-music world of mine, Shakti is probably the finest moment of music that I was ever involved in. For something to be accepted as a landmark, it has to stand the test of time. And Shakti has. It wasn’t some volcanic reaction but a pebble dropped into the pond and the ripple effect is only reaching us now,” says Hussain. The band will embark on their India tour in 2023.

Hussain’s visit this year also comes at the back of sexual abuse allegations that have hit the world of classical music and dance. Hussain says that back in the day, the abuse was couched as part of the training journey. “Yes, the abuse was probably rampant, but, and I feel ashamed even to say this, that probably our mindset was to accept it as the norm. The generations now have found it okay to speak about it and thank god for that,” says Hussain, who adds that when he thinks of it now, he wonders if he may have been “nasty” to some women friends or even artistes he was accompanying. “I have come to the conclusion that I may have crossed a line and now I am struggling with how to put that into words to correctly convey my sorrow for whatever might have happened. These are things that make you look in the mirror and ask yourself that question,” says Hussain.