“Let me sing you the songs you are longing to hear,” Patrick Haggerty offered fondly during his waltz-time ballad “All Disillusions Behind” on Lavender Country’s second album Blackberry Rose. He was singing to a lover — “It’s kinda corny,” he winced and chuckled during a promotional documentary — but by then, he was also addressing an audience he once doubted he’d ever have.

When he died at age 78 on Monday — Lavender Country’s official Instagram account confirmed that he died of complications related to a stroke, “surrounded by his kids and lifelong husband, JB” — Haggerty was celebrated as a pioneering elder by LGBTQ+ artists, activists and fans who stake their claims to roots, country and folk music. But it was just in the last half-dozen years or so that Lavender Country’s debut — the self-titled, 10-song set he and his original bandmates made back in 1973 — enjoyed wide recognition as the first openly gay country album.

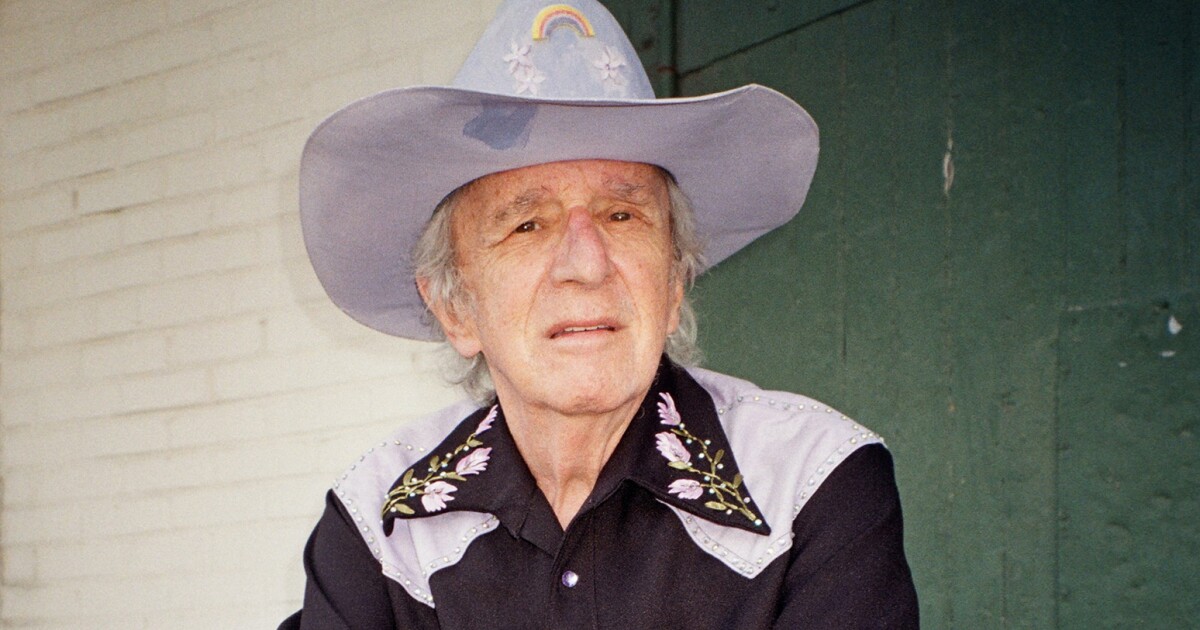

Making those kinds of claims to firstness is a complicated thing. As a number of history-revising scholars, including Nadine Hubbs and Ryan Lee Cartwright, have noted in their work, and as queer, banjo-playing songwriter and thought leader Justin Hiltner makes clear virtually every time he speaks on the record, “queerness in these rootsy, country, and rural spaces is nothing new.” But the arc of Haggerty’s career, the chance to witness a warmly uncompromising and incisively charismatic figure revive the life-endangering truth-telling he did during the Stonewall era while occupying the spotlight in a lavender-hued snap shirt the final eight years of his life — that was monumental.

The many interviewers who asked Haggerty what he thought about gaining new generations of musical followers in recent years often received a playfully pungent response. “For years I was by myself,” he told Billboard in 2021. “Now I have an entourage of country performers who think I’m their grandpappy or something.” He also tended to scoff at the question “Why country?” as though it ought to be self-evident that a boy who grew up in a Hank Williams-loving, dairy-farming household in Washington state and went on to become an openly gay and politically radicalized man would reach for country songwriting as a tool of agitation.

Haggerty made clear that his wasn’t the story of a country hopeful who tried to break into the business. He was acutely aware that songwriting advocating for a Marxist and intersectional vision of gay liberation would be unmarketable in almost any genre in the late ’70s. What enabled him and his musical co-conspirators Michael Carr, Eve Morris and Robert Hammerstrom to make that first Lavender Country album, and press 1,000 copies of it, was the grassroots funding they received from Gay Community Social Services of Seattle, where they lived. That’s also how they secured a P.O. Box, placed ads in the back of magazines and commenced a modest mail-order business.

In a promotional clip for a re-release of the album decades later, Haggerty scoffed at the notion that he was fazed by any controversy his version of country generated. What he cared about was the queer folks who bought the LP in secret and listened in tearful appreciation as he merrily and explicitly took down straight, white, cis toxic masculinity (“Cryin’ These C***sucking Tears”), decried how the forces of capitalism divided and conquered working-class activist coalitions and delayed gay liberation (“Back in the Closet Again”), immortalized the pleasure and anonymity of a cruising encounter (“I Can’t Shake the Stranger Out of You”) and imagined a welcoming queer utopia where there would be no policing of gender performance (“Lavender Country”). Haggerty was writerly and purposeful about his outrage and outrageousness, drawing on the traditions of protest folk and high camp. Over shambling, spirited, piano-driven and fiddle-accented country-rock, he hit his notes head on, needling listeners with his penetrating wit. His rough, reedy timbre made no concessions to uptown, cosmopolitan expression, but he certainly knew how to ham it up.

After half a decade of performing in the Pacific Northwest, Haggerty felt marginalized in his own political movement, too radical for the gay rights coalitions forming with Democrats. He set the band aside and moved on with his life’s work: co-parenting, marriage, campaigning for local and state office, working for quality of care and policy change for AIDS patients.

The first Lavender Country album fell out of print and into obscurity, until a crate-digger uploaded “Tears” to YouTube and the indie label Paradise of Bachelors reissued the full-length in 2014. After it became available more widely than it had ever been, performers making their ways down a variety of paths latched onto Haggerty’s songs and story. High-profile drag queen Trixie Mattel wanted to duet. Masked crooner Orville Peck offered an opening slot. At a number of queer country showcases, Haggerty was both honored guest and headliner. When Blackberry Rose, the second Lavender Country album, saw a wide release by Don Giovanni records in 2022, musicians who saw themselves as working in that broad lineage — like Mya Byrne, Paisley Fields, Lizzie No, Jett Holden, Mali Obomsawin and Austin Lucas — collaborated with Haggerty, some providing backing on the record and others joining Lavender Country on a package tour this past spring.

For Haggerty, though, any interaction with the music industry itself remained fraught. His mind was still fixed on the movement. “You’re supposed to stand on my shoulders and move forward,” he insisted to the online magazine Country Queer, “because that’s what’s going to be required of you to see the Revolution through.”

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.