Brian Eno has been involved in so many varied and significant musical adventures that to call him a Zelig-like figure — which is often done — is to risk understating his reach and importance. The English musician and ideas man helped birth glam and art rock as a member of Roxy Music. He had a strong hand in iconic works by David Bowie, Talking Heads, U2 and Coldplay. Across a series of his own influential albums he pretty much invented ambient music. Eno’s clutch of nonambient solo albums are by turns nervy, catchy, enigmatic and moving. And so he has gone, fruitfully hither and yon, up to his latest, this fall’s “FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE.” (Listening to the album, with its musical evocations of technological decay and natural resilience, while my commuter train rumbles through swampy New Jersey industrial blight has often turned my usual emotionally inert trip to the office into a roller coaster of despair and acceptance.) Oh, and Eno, who is 74, has also led a parallel career as a roving music theorist-slash-public intellectual, one with a newly urgent focus. “I’m thinking about what most other people are thinking about now,” Eno says, “which is climate change and the threat of the collapse of civilization, which seems to get a year closer every two months.”

I know that over the years you’ve asked yourself, in a self-critical way, whether your work is really worth doing. But now, at your age, the bulk of the work is done. Your time has mostly been spent. Knowing that, do you feel like your answer to that question — which is the question of how you’ve lived your life — has been satisfactory? I think I’m still answering it. I’m still working on it. I’ve wanted to write a book for a long time: Why does art exist? Why do we have aesthetic preferences? There are all sorts of ways of explaining this. Some of them are biological: We like things that are red because it’s the same color as blood and sex organs and that sort of thing. But there are much more interesting ways of saying what the role of art is in the maintenance of a society. I don’t want to die before I get that done. [Laughs.] What I want to say is that culture — art, if you like — has an important set of functions in preparing us for the future. If you read a book like “1984,” you’re surrendering to a world with certain values and attributes and seeing what it feels like. Then, when you see something a bit like that starting to exist, you have a way of understanding it and how that might feel.

I get how what you’re saying makes sense for a novel like “1984,” but how does it make sense for art forms like nonnarrative music, which you make, or abstract paintings? That’s the most interesting question you could have asked. I’m absolutely fascinated by this question, because I think I have an answer, and I don’t think it has ever been well answered. What happens when you go look at a painting you’ve never seen before? What I think happens is that when you look at that picture, you’re seeing it in the context of all the other pictures you’ve ever seen. When you go and look at something new, what you’re saying is, “What’s different about this experience?” In many instances, there won’t be anything different, in which case you’re not that interested. But if you can look at it and say, “That’s more angular. That’s fuzzier. That’s much more this, much more that” — we’re very good at understanding differences in feeling within our own long narrative of looking at pieces of work. But what does it mean, for example, when a picture is scratchier than another? You read that as, This is urgent. The artist didn’t have time to make it pretty. We read messages that don’t have a text quality to them, and we still pick up on the ideas that make them different. Or take Bauhaus. When Bauhaus comes along, it’s saying, “We no longer think of the world as divided into beautiful things and functional things.” That’s a philosophical position about the world. Art, even when it’s nonnarrative, makes those kinds of points all the time.

Brian Eno, right, with fellow members of Roxy Music, 1972.

Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns, via Getty Images

You have ideas about how art does what it does. Do you also have ideas about what makes artists what they are? I’m thinking about something like charisma. What is it that makes some of the people you’ve worked with — Bryan Ferry or David Bowie or Bono or David Byrne — into stars? What accounts for that quality? That’s an interesting question. I think charisma comes out of the sense you have that not only is somebody different but they’re also confident about it, committed to it, obsessed by it even. We don’t find uncertainty charismatic. Uncertainty doesn’t work for anybody very well, because in general the media don’t appreciate people like that. I would like to cultivate a charisma of uncertainty, a charisma of admitting that you’re making it up as you go along. I remember this funny thing. One day when we were working on the Passengers album with U2 in Dublin, Pavarotti came into the studio because he was singing on one of those tracks. We’re in the main room saying, Should we put the chorus here, no, let’s double that section, da da da. Pavarotti’s standing in the control room watching what we’re doing. Then he says, “You are making it up!” I think it was the first time he realized that, at some point, music is made up!

As opposed to not just springing out fully formed? Exactly. It doesn’t come as a whole package and then you learn to sing it. I thought, If he was surprised by that, how much more would other people be surprised by this notion that things are born messily? They don’t come out with any charisma at all. They start out, they’ve got blood on them, you’ve got to clean them up, surround them with love and attention until they can stand on their own. Yeah, a charisma of uncertainty would be my thing. In a way, David Byrne has that. One of the attractions of his persona is that he’s not afraid to weave in confusion: “How did I get here?” I think he’s on a path to a kind of feasible future human. You can be amazing, but you could admit too that you’re bewildered.

Since we’re talking about how things work: How do you want your new album to work for people? I suppose I’m trying to make a space where people can rest their attention in one place for a while. One of the epidemics of now is the inability to focus or concentrate. I was watching someone at lunchtime today. She had a book and was on her earphones and on the phone. There could be a postmodern argument for saying that this is a new way of absorbing and collaging material together. I personally find that quite hard to do. I’m addicted to the idea that you put yourself in a place and surrender to it. It’s about making space for a kind of attention that you’re not normally offered by entertainment media. The other thing is that if you’re writing things, and they have words, and therefore suggest the possibility that they are about something, then what are they about? Although this isn’t an album about climate change, it’s an album made by someone aware of living in the era of climate change.

David Byrne, left, with Eno in the recording studio, circa 1978.

Roberta Bayley/Redferns, via Getty Images

Along those lines, there’s beauty in your new album, but it’s also deeply sad. Is that an accurate reflection of how you’re feeling about the world? For me, some of the music is very blissful. The last track is an idea of a kind of future that I would like. Also the track called “We Let It In” is not pessimistic. There is a threat built into it — that low barking sound — but that’s because I can’t conceive of a future where there isn’t a threat. I think we’re in for a hard ride for maybe half a century. Then it will either be the end of civilization or a reborn humanity with a different set of ideas about who we are and where we belong and how we must relate to things in order to survive. So I see a pessimistic short-term future. Not short-term for the person who’s living it but short-term in the history of civilization. Then I see this point at which we either really fail or we start to succeed. I think the succeed side has a very good chance because of the amount of human intelligence at work. There has never been more intelligence on the planet than there is now. Not only because there’s more brains than ever but there are also more augmentations of brains. There are more connections among all these brains. We’re in a sort of intelligence explosion. I hope.

It doesn’t always seem like it. No, it certainly doesn’t. [Laughs.]

An idea that has gained traction lately is that we’re in a particularly boring period of popular culture. People have suggested certain structural reasons for that, having to do with, for example, an increased disinclination toward ambiguity. But what about you? Do you think we’re in a dull cultural moment? I don’t, actually. Right now I see quite strong movement in some rather unexpected areas. A.S.M.R., this whispering thing, that’s incredibly promising. It’s quite counterintuitive. You get the idea that the trajectory of media is greater acceleration, louder, more surprises, and here you have millions of people sitting listening to somebody brushing their hair and whispering for 40 minutes. You have to take that on board as being one of the things that’s happening in culture and quite different from the story that we’re generally hearing. LARPing, too. I don’t think many people take that as seriously as I do. It’s an extraordinary new art form. Quite alarmingly it seems to be developing into a political form as well. Live-action role playing is what we now call politics. So it has a downside as well.

Eno at Air Studios in London in 1973.

Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns, via Getty Images

Have you LARPed? I’ve done limited, party-game versions of it. I love those but I’ve never done it on a sort of proper scale.

Do you have a LARPing fantasy? Yes! Did you read Kim Stanley Robinson’s most recent book?

“The Ministry for the Future”? Yeah. That would be a great thing to do some LARPs from. I’d love to be the black-ops specialist in that book. I’m always interested in these nonconforming areas where a new story is being told.

You once wrote — this was almost 30 years ago — that you were frustrated by the available pornography. Is that still the case? No, no! Because it’s been democratized. You now have sites where people put up their own stuff, and it blows that Los Angeles pink stuff out of the water. The dominant colors of L.A. porn are pink and honey. It’s glossy, shallow, no shadows. You know the form called outsider art? It thrills me. That same attention of naïve artists has been turned to porn. There’s some incredible stuff coming out. It gives you faith in humanity. Jesus, there’s a lot of clever, passionate people out there.

Hey, is it really true that you peed on a Duchamp? Yes I did.

Really? No security guard saw you? No. In fact there was a security guard standing within two meters of me when I did it but he had his back to me. The way I did it was rather complicated. I noticed that this vitrine that the urinal was in had two pieces of glass about five millimeters apart — there was a tiny gap. So I went to a plumber’s near the Museum of Modern Art and I found some fine plastic tube that I knew I could get through it. I used that and a pipette. I went to the toilet and peed in the sink — God, they’d hate to know this. I pipetted it up, covered the end so it held the golden liquid in there, and then stood by the vitrine and was feeding the pipe through. I mean, it was symbolic in a way because it was a tiny amount of pee.

You weren’t worried about damaging the priceless art? No. I didn’t think my urine was that acidic.

Maybe this is semi-related: Smell anything good recently? Two things. One is a neroli, a bitter orange blossom. Somebody made a version that’s got limonene, citronella and something called hydroxycitronellal. It’s the best-smelling neroli I’ve ever smelled. The other one is a smell I’ve known about for a while but I’m getting back into. It’s called karanal. It makes you think of ozone. You know when you click a stone and a piece of metal together and there’s that smell? I send away for these things and they come back and I sit and smell them. I’m filling out in my head the map of smells. Triplal is another beautiful one. I love it.

David Bowie, Bono and Eno backstage at Royal Festival Hall in London in 2002.

KMazur/WireImage, via Getty Images

I wanted to ask you this: Almost all recorded music now is ambient music, in that it’s used as background while we do other stuff. But it doesn’t quite feel like musicians are responding to that reality in any especially interesting ways, at least as far as I know. Is there more that musicians could be doing there? There’s certainly more to be done. The whole point of ambient music was to say, look, it’s not as if people were going to sit down in front of their speakers and focus. Even in 1978 that wasn’t what people were doing. People wanted more consistent, longer-lasting moods. They didn’t want what albums were offering, which was a dance song, a ballad, another loud song and then a quiet song — that idea that you’d get bored with something that didn’t have a lot of changes. But every way of listening produces a new music. What I’ve become interested in is listening clubs, where people get together and listen to a record. This strikes me as a very interesting development. There are strong signs that people are resisting the atomization of everything. It’s suited capitalism to have us all as separate as possible because then we have to all buy things individually. People are getting fed up with that and wanting to do things together. One of the things they’re wanting to do is to start tackling climate change. I think this is the biggest movement in human history, but it’s hardly noticed by the media. There are millions of people involved in some way working on climate change. This huge movement is starting to coalesce.

You’re obviously interested in how the world might change or be made to change. I’m curious about what you think of the idea of “disruption,” which is a word that the tech world has basically ruined. It depends how it’s used. For people like Steve Bannon, destruction is their main tool. That famous statement he said: “Flood the zone with [expletive].” This is more and more what populists do. They think, OK, if we can create chaos, we know how to benefit. Because in chaos people retreat to those who look like they’re certain. The thing that populists project is: We all know what’s going on, don’t we? Too many immigrants or Jews or liberals. This is why I talk about the climate movement, because that’s anti-chaos. That’s a knitting-together of people. It’s just starting to show a few green shoots, but underneath the ground there’s this constant thickening. I went to a conference the other day in Barcelona, and there were, I don’t know, 500 people. There are 20 whom I’ll probably have further conversations with. I thought, How many conferences of that scale were going on that weekend? Probably worldwide it would have been maybe 150. If everybody in those conferences was making roughly the same number of connections — I get this picture of this movement becoming powerful. You start to think, We’re all doing it. It’s not the David and Goliath situation we’d thought it was because, actually, we’re Goliath. We’re not David.

Eno protesting the war in Afghanistan in 2012.

Mark Davidson/Alamy

Insofar as you have a public image, it’s as an extremely cerebral figure. But even just in this conversation it’s clear that emotions and feelings drive a lot of what you do. So what’s an emotion or feeling driving you right now? I can give you a clear example. I recently found this gospel song on YouTube. Donald Vails is playing piano on it. Billy Preston is playing organ. They’re in a room with a mixed bunch of people with quite a range of ages. They sing this song, “You Can’t Beat God Giving.” It’s a great song, but what’s fantastic is seeing these people singing to one another. It’s intensely moving. Billy Preston is sort of sitting in as a star, but the rest of the people, I would assume, have normal jobs and normal lives, and they’re elevated by this community they’ve formed around this event. That, more and more, is the feeling that I’m fascinated by: What happens to humans when they multiply their feelings together? We’ve been so atomized over the last 50, 100 years and told that we have to have our own completely independent lives and that the real human is the one who can stand alone. The real human, to me, seems like the one who can support his neighbors and work with them. That’s a feeling that I pursue. Whenever I see it, I want to encourage it.

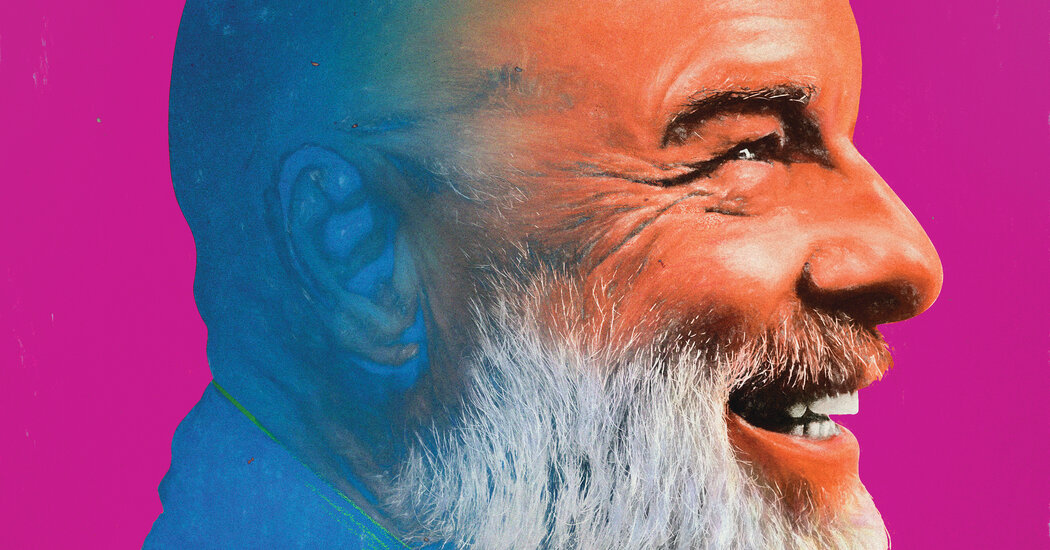

Source photograph for the illustration above by Kalpesh Lathigra for The New York Times.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity from two conversations.

David Marchese is a staff writer for the magazine and writes the Talk column. He recently interviewed Lynda Barry about the value of childlike thinking, Father Mike Schmitz about religious belief and Jerrod Carmichael on comedy and honesty.