This text is an expanded version of the article originally published (in Estonian translation) by Sirp, 16 September 2022.

It’s surely true that no composers today – and very few composers historically – would give any credence whatever to the so-called “curse of the ninth”, the absurd superstition that, having written their ninth symphony, a composer is doomed to die before completing any more. Yet it’s interesting to note that, since the time of Joseph Haydn (who not only established the symphonic form but also set the bar ridiculously high, with 104 of them), relatively few people have composed more than nine symphonies. There are, of course, notable exceptions, among them Henze, Panufnik, Pettersson, Maxwell Davies and Shostakovich, as well as the Estonian Eduard Tubin, who over the course of a 40-year period established himself as the country’s greatest symphonist, composing 10 symphonies. (He died before completing his eleventh; make of that what you will.) Tubin’s compatriot Erkki-Sven Tüür has now equalled this total following the completion of his Symphony No. 10, which received its world première in Bochum in May this year, and its first Estonian performance a few weeks ago by the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra.

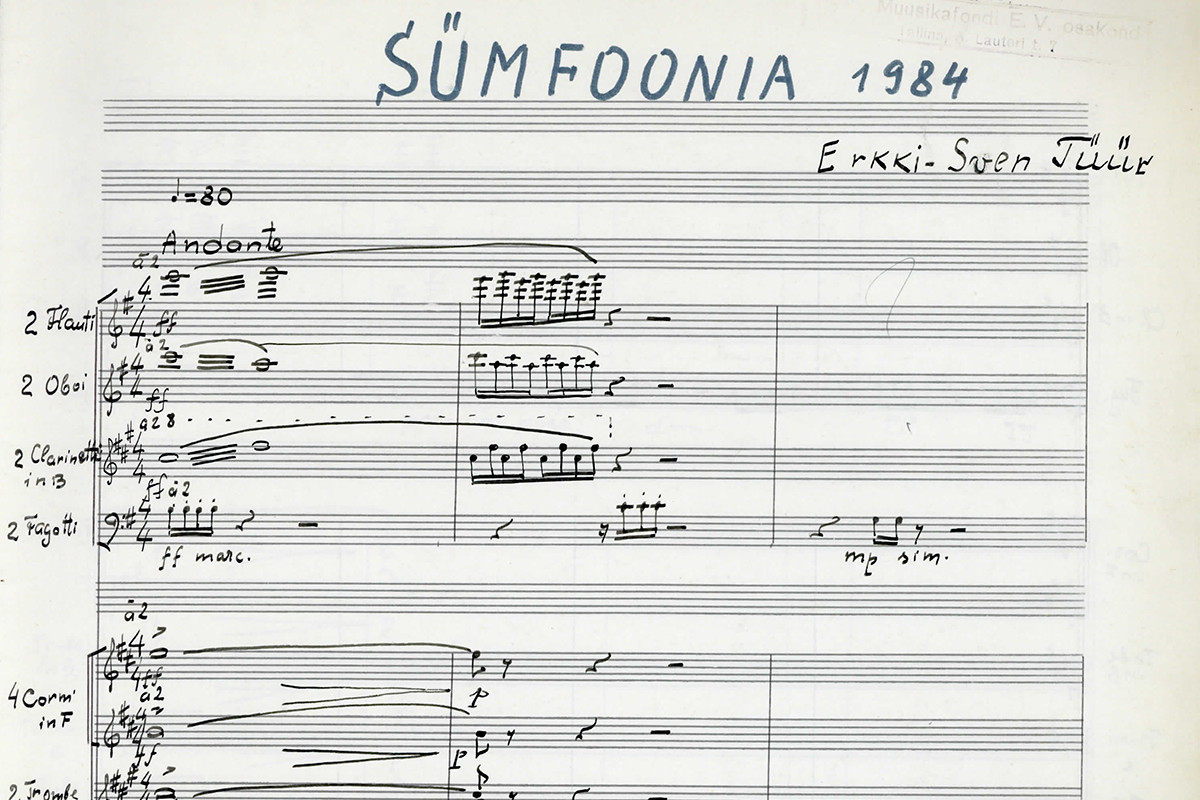

Born in 1959, Erkki-Sven Tüür’s symphonic journey began while he was still a student. His Symphony No. 1, completed in the spring of 1984, was submitted as part of his final coursework at the Tallinn Conservatoire. Tüür evidently already had concerns about the work – which was his first orchestral composition – consulting privately with fellow composer Lepo Sumera for advice and guidance. Despite useful feedback from Sumera – “He took my score for couple of days and wrote a good deal of suggestions and questions” Tüür told me recently – he nonetheless remained unhappy with the piece, withdrawing it following its first performance in November 1984. It would remain unheard for a further 36 years, until Tüür unveiled a heavily revised version of the symphony completed in 2018, which was given its première in February 2020.

Ordinarily, one would look to an early work like this to find examples in the young composer’s musical language that point to the future, signs and traces of that would subsequently develop. But in the case of Symphony No. 1, such an examination is complicated by the fact that the work has been revised. The situation would be less problematic if the revisions were slight, but for much of the work they are very extensive indeed, such that it can be argued that the symphony as it now stands, for the most part, no longer meaningfully represents Tüür’s musical thinking in 1984 but in 2018. (As such, being revised after his Symphony No. 9, would it be more accurate therefore to refer to it as Symphony No. 9a?)

The two outer movements, containing the most lively music in the symphony, are where the revisions are most extreme. In the first movement, Tüür’s approach has been to greatly reduce the musical material, to the extent that its original duration of a quarter of an hour has shrunk to less than seven minutes. The original movement had a three-part structure, beginning with a long introduction, sounding rather like a procession, underpinned by a recurring two-note motif most often played by a suspended cymbal. The end of the movement returned to this mood, somewhat treading water with vestiges of the earlier material gently heard for the final time. Both of these sections have been cut completely from the revised version of Symphony No. 1, Tüür refocusing the opening movement on just its 6-minute central portion, where the tempo picks up and the music becomes rhythmically energised. However, while the character of this middle section has been retained, it has been extensively reworked such that it is almost unrecognisable. The original movement takes nearly five minutes to move past the introduction and get its pulse going, before a 7-beat syncopated motif appears, driving the music along, like an obsessive fragment of Morse code over a ceaseless chugging pulse. For the 2018 revision, the tempo is faster and gets up to speed instantly, falling back to rising wind lines before launching into light, string-heavy counterpoint redolent of Tippett’s Concerto for Double String Orchestra. Instead of the Morse code motif, Tüür uses a shorter syncopated idea that soon dominates all parts of the orchestra. On a couple of occasions there’s a possible homage to the removed 1984 introduction, when a suspended cymbal keeps steady time in the background while the primary material rushes past.

If the 1984 version of this movement could be heard to take far too long to get going, the original last movement does the opposite, taking almost no time at all to charge directly towards its main climax. Tüür has therefore sought to expand here rather than compress, in the process increasing its length from six to eight minutes. The 2018 revision uses the same basic motivic material but now allows it time to ebb and flow, oscillating between brief moments where the music subsides before surging onwards. Now when the movement reaches its climax, it sounds much more like the apex of a coherent musical argument, the orchestra letting rip with fanfares, a wild drum kit breaking out, and what sounds like a united howl of exuberance. The curt 1984 ending has also been developed, Tüür nicely clarifying the music into discrete strata before concluding in a similar way to the original, settling over a sustained chord with brief final chirps from the winds.

By complete contrast, the revised central movement is in all important respects the same as the original. This is extremely fortunate, as it is undoubtedly one of the most arresting movements in Tüür’s entire symphonic output. It also has a three-part structure, opening with gentle, lyrical music on strings and harp; occasionally the music becomes halting, its harmonies turning oblique, but each time regains its focus and continues. A legato wind idea starts up, akin to organum, each phrase ending with a repeated note, and unexpectedly this gains more and more strength and soon spreads everywhere. As the orchestra unites behind this idea, the music becomes more dense, the strings start to unleash harsh slashes, and all trace of the initial lyricism is entirely forgotten. What’s happening? How did we get here? There’s something of the dark symphonic trajectories of Shostakovich in the way Tüür takes us so surprisingly far from the place of clarity and certainty with which the movement began. Only when this idea finally reduces in size is the lyrical string melody heard again, as unexpectedly as it vanished, its return seemingly causing the orchestra to pause periodically in rapture, everything becoming briefly suspended.

Though lyricism is hardly absent from Tüür’s symphonies, none of them are as overtly, melodically lyrical as in this early slow movement. From a superficial perspective, it may seem as if the first and last movements – with their energy and momentum – are the most obvious connection between this early work and the nine symphonies that have followed. Yet there’s a more compelling argument to say that it is in the central slow movement – in both its 1984 and 2018 versions – that we find a more essential connection. As we will see, one of the primary features of Tüür’s symphonies is a focus on the juxtaposition (rather than development) of highly contrasting, even conflicting, ideas. In this movement, the nature of this juxtaposition is slow and insidious, though the contrast is considerable and the effect it makes highly unsettling, causing us to ask fundamental questions about what we are hearing, and how and why the music has moved between such radically different types of material. It is precisely this kind of disorientation that typifies much of Tüür’s subsequent symphonic output. (One could also say that the contrast between the dark central movement and the much lighter first and third movements is similarly disorienting.)

The world première of the revised version of Symphony No. 1 took place on 21 February 2020, performed by Tallinn Chamber Orchestra conducted by Tõnu Kaljuste.