This text is an expanded version of the article originally published (in Estonian translation) by Sirp, 16 September 2022.

An extreme example of disorientation caused by juxtaposition – first glimpsed in Erkki-Sven Tüür‘s Symphony No. 1 (in both its original and revised versions) – occurs in the opening part of his Symphony No. 2 (1987). Titled ‘Vision’, the first movement is filled with strangeness – a mixture of rumble and distant activity – where the only clear sound is a bell. This continues for a couple of minutes, until dissonant trumpets suddenly appear from nowhere, heralding an enormous crash, causing the full orchestra to launch into a loud, relentlessly busy, extended sequence. The effect is like an inversion of the beginning of Richard Strauss’ Eine Alpensinfonie, with something like a black sun suddenly exploding into view. The only stable aspect of this sequence is a deep drone far below, holding in place the chaos above. After a few minutes, everything subsides, arriving at a similar music to the start, soft and distant, with rumbles below. We end up asking the same question as in the middle movement of Symphony No. 1, though even more forcefully: what the hell just happened?

Tüür doesn’t so much answer that question as provide a second movement that pushes the idea of juxtaposition to even further extremes. Titled ‘Process’, over the course of its 20-minute duration the music veers wildly between material that can be described as either clear or ambiguous. But which is which? The fast, rhythmic (somewhat minimalistic) material seems to provide certainty, but Tüür often gives it the power and subtlety of a piledriver, complicating it with explosive accents, aggressive repetitions, and harsh clusters. Likewise, the quiet, slithery material at first seems nebulous and unclear, though its gentleness ensures that all the edges are soft, making it sound more tangible and focused.

The reality is that these opposite forms of material are, in different ways, both ambiguous and clear at the same time, which makes the result of their juxtaposition all the more disorienting. (This is despite the fact that, as in the first movement, the different sections of the movement tend to be harmonically static, with their underlying ‘tonic’ often clearly audible.) What Tüür does with the juxtaposition in this movement could hardly be more basic: he simply keeps it going. As the minutes pass, far from familiarity bringing relief, this complex mingling of extreme but confusing contrasts starts to feel more and more overwhelming, surrounding us on all sides with a violent, volatile music that resists our efforts to predict or understand. This is another important characteristic of Tüür’s symphonic writing; similarly long and intense periods of radical juxtaposition appear on multiple occasions in the later symphonies.

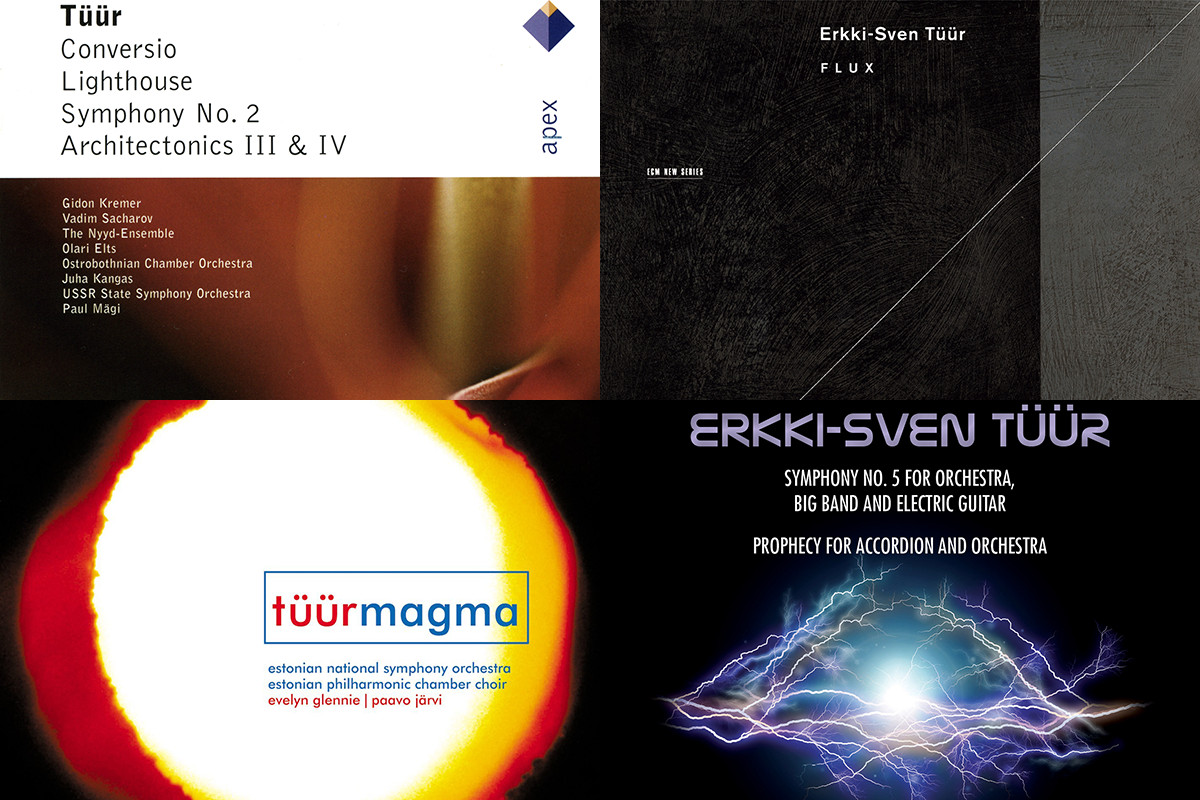

Symphony No. 2 was the first of Tüür’s symphonies to be commercially recorded. Performed by the USSR State Symphony Orchestra conducted by Paul Mägi, it was originally released on Melodiya in 1988. This recording was reissued by Finlandia Records in 1994 and Apex in 2003. Though long out of print, second-hand copies of both of these CDs are available online.

In both of these early symphonies, Tüür’s approach can be thought of as an oscillating juxtaposition, alternating between highly contrasting ideas. (Indeed, even the titles of the two movements in Symphony No. 2 are stark contrasts: the involuntary passivity of a ‘Vision’ answered by the deliberate activity of a ‘Process’.) In Symphony No. 3 (1997), however, this approach is developed into a parallel juxtaposition, where contrasting ideas are presented simultaneously. However, it is not immediately obvious that this is where the music is going.

In the first movement, ‘Contextus I’, Tüür takes time setting up a variety of discrete ideas, including a kind of ‘ghost jazz’, filled with soft suspended cymbal strikes and a network of pizzicati; a cloud of rapid, individual woodwind lines; boisterous, dissonant brass; and rhythmic strings with a strange, distant rising or falling, followed either by more winds or a vibraphone solo. It’s the strings that prevail from this steady presentation of ideas, though shortly after Tüür starts to layer up the ideas, placing them side by side, to the extent that the juxtapositions become convoluted and blurred, no longer merely oscillating or interrupting but overlapping and giving the distinct impression of ideas in conflict, pushing against each other.

He explores something similar in the second movement, ‘Contextus II’. Initially, the juxtapositions oscillate between another busy wind texture – by now a firmly established trope in Tüür’s symphonies, prominently occurring in almost all of them – and a slow-moving, octave-doubled string line. At a similar point to the previous movement, additional ideas appear and again start to be heard in parallel, jostling together in a way that starts to feel uncomfortable, most obviously in the collision between lyrical strings and punchy brass. Yet while the nature of this parallel juxtaposition suggests friction and discord, Tüür nonetheless retains the possibility that, being in parallel, the contrasting ideas are not necessarily impacting upon or otherwise affecting each other. They could possibly be simply adjacent parts in a wildly incongruous chorus. As such, the word ‘Contextus’ could simply refer to the way we keep perceiving these discrete ideas differently depending on the ever-changing (clear or ambiguous) context.

While the juxtapositional approach used in Symphony No. 3 becomes more convoluted than before, it nonetheless consolidates the fundamental nature of Tüür’s contrasting ideas, established in the first two symphonies, tending either toward clarity (often melodic or rhythmic) or ambiguity.

Symphony No. 3 was released by ECM in 1999 in a recording by the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Dennis Russell Davies; though nearly 25 years old, it is still in print and readily available.

In both Symphony No. 4 (2002) and No. 5 (2004), Tüür continues these ideas within a relationship between soloists and the orchestra. Subtitled ‘Magma’, Symphony No. 4 also suggests ideas playing out in parallel, here seemingly unaffecting each other, with the solo percussionist (a part originally composed for Evelyn Glennie) riding on top of them, either wildly embellishing these ideas or following her own path in the foreground.

When writing about this symphony following its performance at the 2018 Estonian Music Days, i commented on the “vast volcanic scale of the work [and] the sense of awe that it projected”. In no small part this is due to the several occasions when Tüür again allows his convoluted juxtapositions to continue for long periods of time, making it easy to feel not just awestruck, but also lost in the midst of such a welter of simultaneous, and therefore only half-tangible, trains of thought. Importantly, though, the soloist’s role at times acts as a foil to this disorientation, either as a locus of stability in the midst of apparent chaos or as a catalyst for partial or complete orchestral clarity. The work thereby demonstrates a subtle but significant shift in Tüür’s use of juxtaposition, now enabling – via the soloist – the possibility of collaboration between the symphony’s contrasting elements.

A recording of Symphony No. 4 ‘Magma’ by the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Paavo Järvi, with the work’s dedicatee Evelyn Glennie as percussionist, was released by Virgin Classics in 2007. This disc is out of print but copies can still be found.

Symphony No. 5 features an electric guitar soloist in addition to an entire big band as a concertante group. The concept of contrasts is expanded here to encompass both notated and improvised music as well as stylistic differences. Continuing the idea of juxtapositional collaboration heard in Symphony No. 4, Tüür has referred to this coming together of diverse elements from jazz, rock and classical as “trilateral negotiations in a constructive atmosphere”. That description suggests openness, perhaps even sympathy, though the reality is more complex and argumentative.

Indeed, the first movement is not far being a shouting match, with the strings, winds, brass and band all having their own, entirely separate, gestural ideas, the music being the turbulent result of them all being thrown together in close proximity. Again it falls to a soloist to facilitate unity, which comes with the grand entrance of the electric guitar at the start of the second movement. Its extensive solo, essentially silencing everyone else, at first seems like a red herring, being yet another contrasting element with no obvious connection. But it proves catalytic; immediately thereafter there’s a sense of the orchestral sections (principally, at this point, strings and winds) acting with regard to each other. Having been silent, the band comes to the fore in a showcase third movement, now supported and embellished by the orchestra. This is extended through the final movement, leading to music full of confident swagger, though once again Tüür demonstrates his willingness to effortlessly brush aside bold, powerful ideas in favour of much less assertive material, in this case arriving in a dark place full of unsettling, hovering chords, with guitar notes sliding strangely in the middle distance.

Symphony No. 5 was released by Ondine in 2014 in a recording featuring Nguyên Lê on electric guitar and the UMO Jazz Orchestra alongside the Helskinki Philharmonic, conducted by Olari Elts.