It’s time we stop canonizing average punk albums of the classic era. The Sex Pistols‘ debut record, Never Mind the Bullocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols (1977) is an example of the way hype and marketing centered on rebellious youth culture helped forge a convenient origin story for punk around a fairly ordinary set of tracks.

Punk emerged in the US and the UK in the second half of the 1970s as a reactionary force against the commercialized nature of rock. Major acts including the Rolling Stones, Rod Stewart, Pink Floyd, and Elton John, who played to stadium-sized crowds earning large sums of money in the process, appeared out of touch. Writing for The Guardian in late 1976, Steve Turner described the disaffection of English fans in the following way: “They’ve all grown up with a music that they felt alienated from — groups too old to identify with, musicianship too sophisticated to ape, concerts too expensive to attend, and songs that were no reflection of their feelings or problems.” Excesses, stardom, and slick production equaled a loss of connection to the youth culture central to rock.

The Sex Pistols stood at the center of a “new wave” of music that desperately wanted to break away from the decadence of the old guard. Progressive rock acts such as Yes, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Genesis, and King Crimson, had for years pushed the boundaries of rock by merging highly complex musical arrangements that fused jazz, folk, and classical genres with elaborate costumes and staging as well as imaginative lyrics that evoked otherworldly places. Punk rock spit at that very notion. An illustration that appeared in Sideburns, a British fanzine launched in 1977, captured the punk sentiment that dealt a death blow to mid-1970s rock. The figure included three guitar chord shapes in tablature with a caption next to each one reading, “This is a chord [A]. This is another [E]. This is a third [G]. Now form a band.” Punk, in other words, served the inexperienced, the underdog.

Between 1976 and 1978, releases from emerging US and UK bands embraced punk rock’s straightforward approach. The Clash and the Ramones launched the genre’s deadliest salvos with an onslaught of distorted guitars played at breakneck speed. While the Ramones wrote about partying, domestic violence, and drug use, the Clash tackled social issues tied to race, class, and economic depression. Writing for the Village Voice in March 1977, Mary Harron described the differences between English and US punks in terms of goals, sentiments, and style.

In the US, the New York music scene typically associated with punk represented more of an underground movement meant to give artists without contracts forums to play. “American bands take themselves less seriously, but they can afford to,” Harron wrote, because “the USA is still a rich country where to be young, white, and on your own is to be privileged.” Bands such as Blondie, Talking Heads, and Television carved their own niches by drawing from other musical genres including funk, jazz, pop, and reggae.

But to music critics, the disparaties between punk’s two poles on either side of the Atlantic had their roots in social and economic conditions. Toby Goldstein pointed very candidly to this difference in the February 1978 issue of Crawdaddy noting youth in the US wanted “to rock ‘n’ roll all night and party every day, with a good solid job to pay for its pleasures.” Ironically, as much as the Sex Pistols made a name for themselves with their provocative anti-establishment lyrics, their drunken and excessive behavior had more in common with their US counterparts than critics wanted to admit.

In England, punk emerged from working-class London suburbs. “Their music is not ironic or conceptualized,” wrote Harron, “and it draws its impact from the fact that the musicians really are deprived, hostile, and unschooled.” The anger and violence later associated not only with the Sex Pistols but with punk, in general, had its origin in class differences. Estimates calculated unemployment rose to nearly 36 percent for those under 25 years of age during that time period.

Bands such as the Damned, the Vibrators, and Wire emerged from and wrote about living under these harsh economic conditions. The Jam‘s 1977 debut single, “In the City”, spoke with energy and conviction about the “golden faces under 25” and “all the young ideas” thwarted by fear and misunderstanding. That the Pistols drew inspiration from this song’s chromatic motif for “Holiday in the Sun”, the lead track to Never Mind the Bollocks, helps to situate the album in its proper place and time.

We can trace the Sex Pistols to a clothing shop in London’s Chelsea district owned by Malcolm McLaren, the band’s manager, and designer Vivienne Westwood. Inspired by biker clothing, bondage, and the looks of the rebellious youth of the 1950s, the boutique known from 1974 to 1976 as Sex, greatly influenced the punk aesthetic. Westwood’s ripped tees incorporated swastikas, naked cowboys and footballers, printed breasts, and political figures with piercings, images meant to provoke and disturb the sensibilities of mainstream society. Paul Gorman, McLaren’s biographer, told Dazed in 2014, that the Pistols’ manager “quickly realized the potency of popular music and fashion. Once you put the two together you get some kind of combustion.” The London clothier and entrepreneur played a pivotal role in positioning the band at the front of the punk movement.

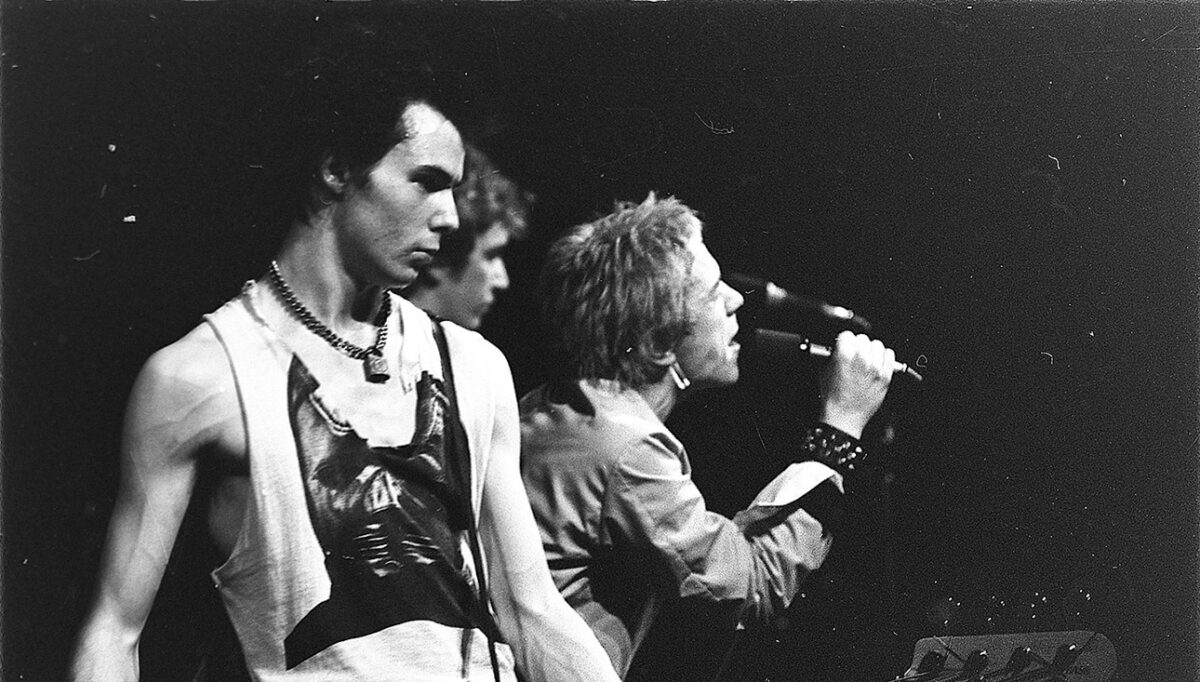

The addition of John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten, in 1975 gave the band the edge they sorely needed. “Johnny’s singing technique, like his phenomenal stage presence and sense of style,” wrote Caroline Coon for Melody Maker in 1976, galvanized the Sex Pistols. Guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook had played together since 1972; bassist Glen Matlock joined them in 1974. The band started to perform live soon after Lydon’s arrival, and by early October 1976, they had signed a recording contract with EMI.

Their first single, “Anarchy in the UK”, a three-minute anti-establishment manifesto, hit the airwaves at the end of November sending shockwaves throughout the musical community. In an interview after this single’s release with Nick Kent from New Musical Express (NME), McLaren declared the song represented “a call to arms to the kids who believe very strongly that rock and roll was taken away from them”. While the single reached number 38 on the UK charts, the label dropped the Sex Pistols less than two months later after they engaged in an exchange of profanity with a drunk television morning host.

The interview for NME revealed the plasticity of McLaren’s vision of punk. Kent characterized McLaren as a mixture between an artist and a trickster attempting to create a postmodern collage out of clothing, music, and irreverence. In McLaren’s version of punk, youth wore rubber, leather, and ripped shirts, they pierced their bodies and invoked violence through actions and lyrics. The critic attended an annual ball hosted by visual artist Andrew Logan where McLaren debuted the band and their entourage. “The strange thing was,” observed Kent, “that it still looked to be a pose – pretty impressive but a pose nonetheless.” Kent’s characterization, an insult to punks who rejected fakeness, spoke to the band’s inexperience, musical and otherwise.

The Sex Pistols practiced, wrote, and played the songs that would appear on the album from 1975 through October 1977 when it finally came out. The lead track, “Holiday in the Sun”, offered a reflection of the group’s short trip to the Channel Islands and Berlin after original bassist Matlock departed in February 1977. “A cheap holiday in other people’s misery, “sneered Rotten before turning his attention to Berlin’s dreariness and the wall that separated East from West after the Second World War. Rotten’s exposure to the militarization he witnessed resulted in chants of going “over the wall” and a general expression of deep anxiety over surveillance.

Never Mind the Bullocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols‘ strength, and part of its endurance, is tied to the aggressiveness and anti-establishment ideas expressed in the songs. Polarizing topics including abortion (“Bodies”), fascism (“God Save the Queen”), political violence (“Anarchy in the UK”), and economic precarity (“Pretty Vacant”) blend with songs about teenage apathy (“Seventeen” and “No Feelings) and distrust of the music industry (“Liar” and “EMI”). In her 1976 interview with the band, Coon described the music as “anti-love songs, cynical songs about suburbia, songs about hate and aggression,” in other words, things their audience could identify.

Never Mind the Bollocks’ most enduring songs each took swipes at power and privilege. “God Save the Queen” dared to challenge monarchical rule and Britain’s notion of empire by simply reflecting the dreary social reality at home. Musically, “God the Save the Queen” sees the Sex Pistols at their best: the tightness of the rhythm section provides the perfect backdrop for Jones’s riffs and guitar accompaniment. Lydon finds the right balance of aggression and melody in his unique vocal delivery, even leading the band at the end of the song in the furious chorus, “no future, no future, no future for you.”

The Sex Pistols experienced considerable growth from their first single, “Anarchy in the UK”, in 1976 to the album’s release at the end of 1977. Jones’ guitar intro on their first single provides a nicely distorted wall of sound to meet Lydon’s call, “right now!” Yet the phaser effect on the guitar during the verses makes the band sound muddied and less menacing. No doubt Jones gained stage and studio experience in the ensuing months because his tone evolved by the time they recorded “Problems”, arguably Never Mind the Bollocks’ most underrated track. Here again, we witness Cook’s tight drumming, fiery guitar work by Jones, and well-executed vocals by Lydon.

The singer’s delivery, a combination of singing, spoken word, and screaming that fit perfectly with the DIY ethos of the punk era, stood in deep contrast to the traditional lead singer expected to belt out high-octave screams or soothing croons. Rotten and the Pistols unapologetically offered neither. At its best (“No Feelings,” “Pretty Vacant,” “EMI”), this style of singing provokes sensibilities and opens numerous opportunities to think about melody and delivery. At its worst (“Liar,” “Holiday in the Sun,” “Bodies”), the stridency and insistence of Rotten’s vocals come off as annoying babbles that distract from otherwise strong compositions.

While attitude and stage presence played a big part in punk, the lack of experience resulted in material that didn’t always provide the excitement of the Sex Pistols’ singles. “Seventeen” and “EMI “seem like repackaged versions of the same song, while tracks like “New York” and “Submission” move at a glacial pace within the highspeed world of punk. Paul Nelson’s glowing 1978 review of the album for Rolling Stone also cautioned readers that the music sounded “like two subway trains crashing together under forty feet of mud, victims screaming”.

Never Mind the Bollocks is a solid album of the punk era. Its lyrics and music evoke the importance of taking charge, challenging authority, and embracing inexperience, all while doing it with loud drums and guitars. Yet aside from a handful of standout tracks, the album as a whole neither reflects the most explosive music of the time nor the most creative. Its value continues to rest on the band’s entangled history with a movement of disaffected youth that wrestled in real-time with the commercialization of their ideals.