Grammy-winning guitarist Jeff Beck dies at 78 from meningitis

Jeff Beck, from the English rock band The Yardbirds, won eight Grammy Awards and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice.

Scott L. Hall and Patrick Colson-Price, USA TODAY

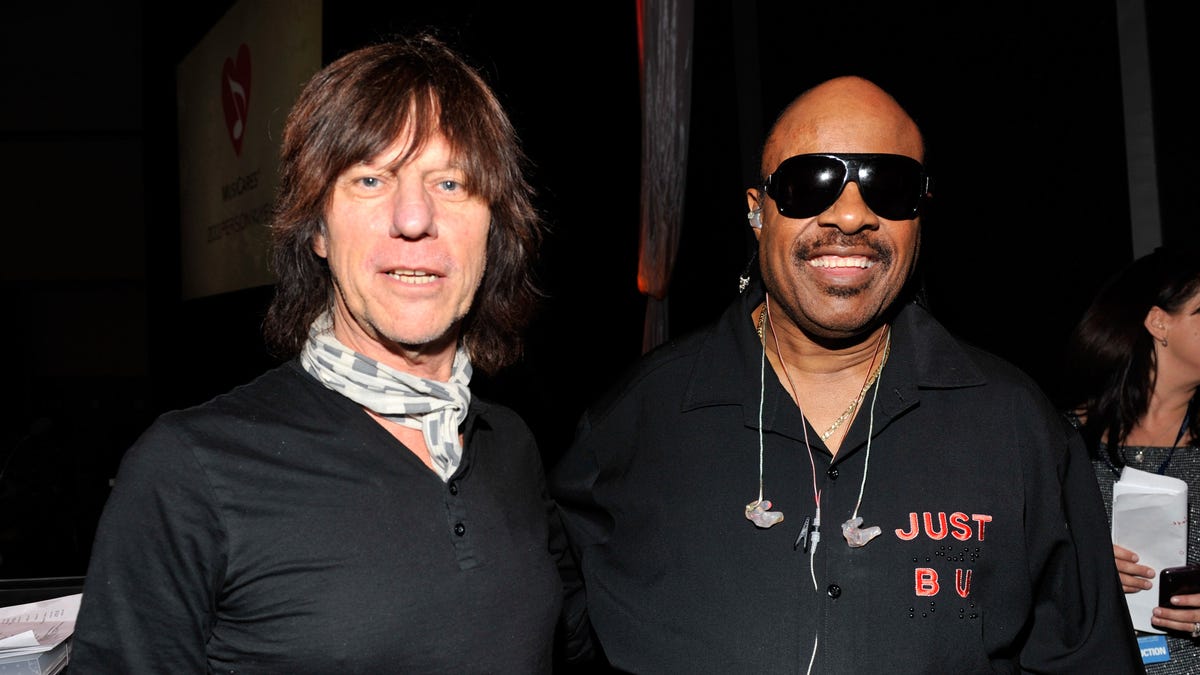

Stevie Wonder had the artistic wind at his back, teeming with creative energy and scaling new musical heights, when he met Jeff Beck in 1972.

Their encounter at a New York studio would soon bear fruit for the young Motown phenom and the British guitar hero — including the enduring “Superstition,” a song that became a signature piece for both artists.

Wonder said Wednesday evening he was saddened by news that Beck had succumbed to bacterial meningitis at a hospital near his home in England. The guitarist was 78.

“He was a great soul who did great music,” Wonder told the Detroit Free Press. “I’m glad that I was able to meet him and have him in my life, giving some of his gift to my music.”

Wonder and Beck were introduced to one another by Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil, producers who had worked with Wonder on 1972’s groundbreaking “Music of My Mind” and were now involved in its follow-up, the album that would become “Talking Book.”

“I really didn’t know too much about him,” Wonder said of Beck. “But then I heard him play in New York. We were working on ‘Lookin’ for Another Pure Love’ (in the studio) and I said to him, ‘Why don’t you play on this?’ He thought that would be great. He laid one part down, then another part and another part. It was just amazing.”

That song — a rippling number that showcased Wonder’s growing fascination with keyboard sounds — was augmented by Beck’s lithe guitar solo, complete with Wonder’s approving “Do it, Jeff!” captured on tape.

“It was just a wonderful thing, the whole deal,” said Wonder. “He gave it such a mixture — sort of a jazz feel with a bluesy feel, with the chord structure he took from what I had done. It was great. He put his touch on it. It was just really cool.”

Beck had sprung from London’s fertile blues-rock scene in the ’60s, making his first big mark with the gritty psychedelic rock of the Yardbirds. But he had an expansive musical vocabulary — jazzy, melodic, sophisticated — that was right up Wonder’s alley.

Like many of his peers, the British guitarist was infatuated with Motown, even heading to Detroit in 1970 to cut tracks at Hitsville, U.S.A., with members of the Funk Brothers. (That material remains unreleased, and Beck told Rolling Stone magazine in 2010 the tapes may be lost forever.)

In New York in ’72, Wonder was thrilled with Beck’s work on “Pure Love.” He and Cecil encouraged the guitarist to record a version of a new, unreleased song Wonder had recently written and tracked: “Superstition.”

Beck saw it as a gift from Wonder.

When it comes to origin stories of songs from that era, details can be cloudy or lost to time. It has often been reported that “Superstition” emerged from an impromptu jam by the two artists, with Beck at a drum kit and Wonder at a clavinet keyboard. But Wonder clarified Wednesday that a rough track of the song was already complete when he first played it for Beck at the studio.

Wonder’s own final version of “Superstition” was a dazzling display of chunky funk, featuring one of the most memorable drum openings in pop music history.

“The first thing I played (for the recording of) ‘Superstition’ was the drums, carrying the melody and all the breaks I wanted in my head,” Wonder recounted. “Then I put on the clavinet, then a second clavinet, then the Moog (for bass).”

Trumpeter Steve Madaio and saxophonist Trevor Lawrence contributed the track’s horn punches.

A friend of Wonder, singer-songwriter Lee Garrett, put an unplanned exclamation point on the song’s bridge.

“He was hanging out in the front of the control room and he kept going, ’Aaagggh!’” Wonder recalled. “I was saying: ‘Shut up, Lee! Shut up! Look, do you wanna be on the record? OK, here we go.’ That was all Lee.”

Wonder’s “Superstition” track, complete with that late-addition “aaagggh!” scream, was headed to Side 2 of his “Talking Book” LP.

Beck, meanwhile, had his own designs for “Superstition,” a song Wonder had encouraged him to embrace. The guitarist was intent on recording it with his new rock trio Beck, Bogert & Appice, and their heavy, muscular version would ultimately appear on the group’s 1973 self-titled debut for Epic Records.

But the October 1972 release of Wonder’s “Superstition,” issued as a lead single at Motown’s insistence, wound up stealing the thunder.

“I told Motown, ‘Listen, I did this for Jeff Beck. He likes the song,’” Wonder said. “I thought we should make ‘Sunshine of My Life’ the first single (from the ‘Talking Book’ album). They said, ‘No, no, no, no. The first single should be ‘Superstition.’ So I went back to Jeff and had that discussion.”

Wonder’s single raced up the U.S. pop and R&B charts — hitting the top spot 50 years ago this month — as Beck and company wrapped up their album recording sessions. Wonder earned a pair of Grammys from “Superstition,” which Rolling Stone ranked No. 12 on its latest 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list.

Beck went on to record another pair of Wonder originals, “Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers” and “Thelonius,” for 1975’s “Blow by Blow.”

Wonder downplays the idea that the “Superstition” release situation caused a deep rift between the two artists (“we had always been cool”), and said he looks back fondly on their performance together at a 2009 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame concert, where they linked up for a sizzling, showstopping rendition of the song.

Wonder said Wednesday he continues to write and record material for his next album, which will be released on his So What the Fuss Music, the label he launched with Republic Records in 2020.

He has also taken to listening back to his older work with his 17-year-old son, Mandla, dissecting tracks and reflecting on the music.

On Wednesday, after word of Beck’s passing, one of those songs played at home was “Lookin’ for Another Pure Love,” featuring Beck’s distinctive solo.

“When I heard it today, it was emotional for me because I could remember the moment,” Wonder said. “There’s just something about music. I know for you, as a fan, songs take you back to a space in time — you’re right there, right then. The same thing happens for us as writers and singers.”

At age 72, Wonder has grown accustomed to losing fellow artists, friends and peers. But he takes solace in his faith in God and his certainty that spirits transcend death.

“As long as you talk about people, you keep them alive,” he said, citing an African proverb. “You keep their spirits alive.”

And an artist’s musical legacy, Wonder said, is part of that conversation:

“We get a chance to hear and feel that spirit, for as long as we can have all the music that motivates people to move forward and do better.”

Contact Detroit Free Press music writer Brian McCollum: 313-223-4450 or bmccollum@freepress.com.