There’s an advert for cruise holidays on television at the moment. It’s all dolphins and dining halls and laughing women flashing their teeth. Above the tinkly swelling music is a familiar voice. It’s the kind of clear English accent that might remind you of a compelling history teacher or vicar. ‘I wonder, I wonder, what you would do if you had the power to dream any dream you wanted to dream,’ he says. ‘You would, I suppose, start out by fulfilling all your wishes, love affairs, banquets, wonderful journeys. And after you’d done that for some time, you’d forget that you were dreaming.’

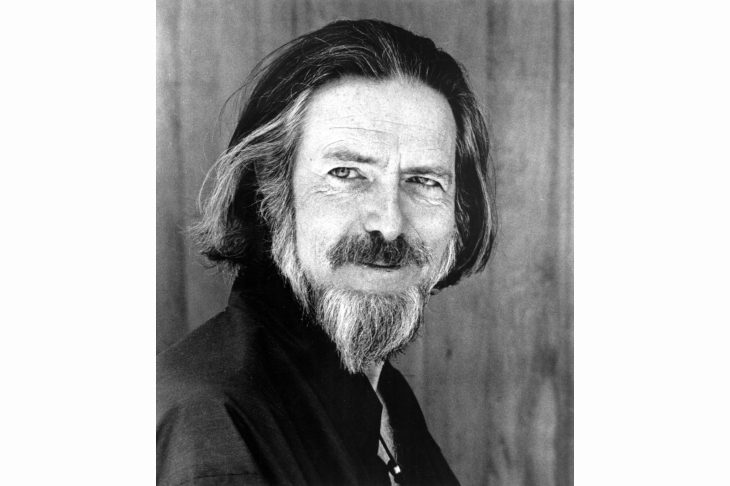

The voice belongs to Alan Watts. He’s a strange choice for a cruise advertisement. Watts was a sixties hippie, a Zen Buddhist pop philosopher who sought to soothe the anxieties of the newly tuned in. Competitively priced holiday packages are not, you’d have thought, a central part of Zen Buddhist teaching. Dig out the full quote and you’ll find that Watts’s words have been edited to remove their true meaning. But nobody really cares.

Watts died 50 years ago this year. Yet British googlers still search for him more often than they do Justin Welby. Van Morrison has written songs about Watts and Johnny Depp is reportedly a follower. The creators of South Park, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, were so taken with Watts that they created a DVD animation series to accompany his lectures. Watts’s voice has been used for a sleep aid app, his little slivers of eastern wisdom interspersed into endless loops of ambient music. In 2017, an indie game called Everything was released using snippets of Watts’s lectures as part of the score. Players controlled a developing universe, directing planets, flowers and atoms as Watts spoke about the nature of the world.

Watts seems perfect for the internet age, even if he died before it. His lectures can easily be broken up into little minute-long chunks, perfect for the limited attention spans of the screen-addled masses. His ideas, too, speak to that typical westerner who likes to describe him or herself as spiritual but not religious. The type of person who dislikes organised religion but thinks there might be something beyond the mortal realm.

Watts hints at the something of Buddhism but never commits to the religion in its full form. For him, the point of faith is liberation; liberation from anxiety and from stultifying western individualism. His credo was individualistic, however, in that he simply picked the bits of faith he liked. The more you listen to his lectures, the more you’ll feel the effects of a kind of sugar-rush philosophy. He was criticised in his lifetime for a lack of commitment to basic Zen practices such as meditation. One can imagine his listeners discovering a sense of clarity as Watts spoke, only to feel it fade as they went back to their everyday lives.

Watts was born on 6 January 1915 in Chislehurst; his father worked for the Michelin tyre company and his mother Emily was a housewife. His maternal grandfather had been a missionary in the Far East and had left Emily a residual Christianity as well as an appreciation for the Orient. Watts’s biographer, Monica Furlong, writes that his mother and her desiccated faith most influenced him: ‘It was not so much that Emily herself had taken on rigid beliefs – she might have been much more cheerful if she had – as that she had been force-fed with them, and had lived with an uneasy and half-digested religion ever since.’ Watts would later say that he had nothing approaching an Oedipus complex, knowing his mother to be kind and generous and yet he felt a sense of unease towards her.

Emily had decorated the family’s sitting room with objects brought home by her father from his missionary work; an Indian coffee table, Korean and Chinese vases and Japanese cushions. Part of the Watts mythology is that he suffered sickness as a child and was engulfed in an oriental fever dream. He was sent to an Oxfordshire prep school in his early teens. ‘A school for aristocrats,’ Watts said, ‘attended by relatives of the royal family, of the imperial House of Russia, of the Rajas of India, and sons of industrial tycoons. There was even a boy who had been buggered by an Arab prince.’ Sexuality seems to be a constant in Watts’s childhood. Part of his dislike for his mother was a sense that she was uneasy with her own body. Another was her obsession with his childhood constipation. Inevitably he hated both his prep school and later King’s College Canterbury, for their ‘militarism and… subtle, but not really overt, homosexuality’.

At 15 he applied to the London Buddhist Lodge, run by the eccentric QC Christmas Humphreys, who would one day become a judge at the Old Bailey. Watts learnt from Humphreys a sort of courtroom style of speech, a syntax that implies logical coherence even when lacking, and a cadence that leaves the listener feeling as though he is being carried along by an inevitable argument. In 1936, at the age of 21, Watts met the Zen Buddhist scholar D. T. Suzuki. Along with Humphreys, it was ‘these three men as much as any who introduced Buddhism to the English-speaking world in the 1940s and 50s,’ according to Buddhist journal Tricycle.

The following year Watts married Eleanor Everett, the daughter of another influential Zen Buddhist from Chicago, and in 1938, Watts and a pregnant Everett left for America. The couple settled into a middle-class New York circle of painters and psychoanalysts but an unhappiness set in. Peculiarly, given his interest in Buddhism, Watts enlisted in an Episcopal seminary in Illinois and attempted to combine elements of Christianity with eastern philosophy. ‘I chose priesthood because it was the only formal role of western society into which, at the time, I could even begin to fit,’ he wrote. He was ordained in 1944 and continued his ill-fitting ministry for another six years. His life in the Church, and his personal life, fell apart when his wife began sleeping with a man ten years her junior. Watts allowed her young lover to move in, a shocking decision for a priest even by modern standards. Eventually, Watts agreed to annul their marriage on the grounds that he was a ‘sexual pervert’.

Like so many 20th century outsiders and wanna-be mystics, he moved to California. He began broadcasting lectures from a San Francisco radio station and soon developed a following, finding a new lover in the poet Jean Burden as well as marrying another woman in 1950, Dorothy DeWitt, with whom he had five children, to add to the two he had with Everett. He would later divorce DeWitt too, justifying his decision by saying that ‘dutiful love is, invariably, if secretly, resented by both partners to the arrangement,’ adding that partners could learn to live with the suffering but that ‘such wisdom may also be learned in a concentration camp’.

Watts’s philosophy is difficult to define. He spoke in aphorisms, linguistically clear but conceptually fragmented reflections on the contradictions of human experience. He rejected the idea of the individual and spoke of the ‘European dissociation’, the feeling of oneself as an outsider in a hostile world. Instead, he argued, we are all the universe and any sense of one’s own desires or exertions are merely an expression of the singular universe unfolding.

In one lecture, Watts explains: ‘As you cannot conceive, possibly, of the existence of a living body with no environment, that is the clue that the two are basically one… You are both what you do and what happens to you.’

It is a strange argument, You can easily imagine an environment without humans. How is it then that nature and human experience can be described as one and the same? But his pronouncements aren’t designed to be logically analysed. It’s a philosophy of vibes.

Over the next decade he drifted in and out of academic institutions, wrote his most popular book The Way of Zen and grew his standing on the lecture circuit. In 1958 he returned to Europe to promote his book but found England weary and uninviting, especially the Cambridge theology department where he was welcomed as something of an oddball. In Switzerland he was introduced to Carl Jung, with whom he discussed the collective unconscious, an idea, he noted, that was similar to the Buddhist alaya-vijnana. Watts spent much of his time in Zurich with a ‘hopelessly psychotic’ woman called Sonya, a dalliance that even Watts regretted, according to his biographer Furlong.

Morality, for Watts, goes the same way as the individual – a false and restrictive concept dreamed up by wayward westerners. Ethics, Watts said, is ‘a part of the universe, it’s a way of playing the human game. But the thing itself is really beyond good and evil.’

In 1964 he married Mary Jane Yates King and struck up another affair with a Jungian analyst, June Singer. Watts’s performance as a father was by his own admission poor: ‘By all the standards of this society I have been a terrible father… I have no patience with the abstract notion of “the child”.’ At the age of 18, he offered each of his children a tab of LSD and guided them through the experience. Thanks Dad.

The collapsing of the individual and the universe into a single entity gave Watts all sorts of get-outs. On psychedelics, he seemed at first reluctant to endorse them, saying that mystical experience is too easy if it ‘simply comes out of a bottle’. But the reticence soon subsided because, he said, such concerns rest on a ‘semantic confusion as to the definitions of spiritual and material’. It’s all one, so what does it matter if you meditate your way to enlightenment or simply blitz your brain with several tabs of acid?

Watts would eventually go on to become a central part of the American counter-culture. In 1967 he brought together the ecologist Gary Snyder, Timothy Leary, author of The Psychedelic Experience, and the paedophile beat poet Allen Ginsberg at the so-called Houseboat Summit. That meeting would come to define the psychedelic utopianism of late-sixties drop-out America, encouraging the young and disaffected to abandon the institutions of modern society and also to take a lot of drugs. In the typically paranoid style of both utopians and those addled by LSD, Ginsberg and Leary warned that a ‘new fascism’ was planning to lock them all up and that the hippie movement faced a ‘concentration camp situation’. Snyder, a close friend of Watts, later said that his writing had become staid, that Watts was going in philosophical circles and failing to meet his potential.

A fellow Buddhist priest, James Ishmael Ford, met Watts in 1969 at a Zen monastery in Oakland. He was unimpressed:

I was enormously excited to actually meet this famous man, the great interpreter of the Zen way. Wearing my very best robes (OK, I only had two sets, one for warm weather, the other for cold), I waited for him to show up; and waited and waited. Nearly an hour later, Watts arrived dressed in a kimono, accompanied by a fawning young woman and an equally fawning young man. It was hard not to notice his interest in the young woman who, as a monk, I was embarrassed to observe, seemed not to be wearing any underwear. I was also awkwardly aware that Watts seemed intoxicated.

There is a sense of knowing in Watts, a kind of overt character contradiction in which he played the raconteur eastern mystic. Aldous Huxley described him as ‘a curious man. Half monk and half racecourse operator,’ a description that Watts reportedly enjoyed. He happily called himself a ‘spiritual entertainer’. In The Book on the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are, Watts writes that the idea of ‘“just little me” who “came into this world” and lives temporarily in a bag of skin is a hoax and a fake.’ He too seemed to see himself as something of a fake, keen to tell his listeners that he was little more than a mischief maker. The result was often a sense of absurdity. In one lecture he attempted to make a serious point, before veering off into self-promotion: ‘If you read the Bible, which is a very dangerous book, as I’m going to be demonstrating in Playboy this December…’ The audience laughed almost as hard as Watts.

By the early 1970s, he had moved to Druid Heights, a hippie commune just north of the San Francisco bay, and was sinking a bottle of vodka a day. Descriptions of his life are sad and chaotic; he was still able to deliver his lectures but when it came to questions from the audience he appeared confused and unable to answer. His first child Joan recounted coming to meet him before one of his lectures and finding Watts hopelessly drunk. He agreed to let her drive him to the lecture but insisted that they stop to buy more vodka. When asked why he drank so much, Watts replied ‘When I drink I don’t feel so alone.’

In 1973, Watts died at Druid Heights aged 58. He had been waiting to give evidence in his son’s trial for drug and other offences, something he found deeply distressing. His wife, who also had a drinking problem, mostly brought on by Watts, believed he had been practising a Zen breathing technique and had managed to leave his body but was unable to return. He was found at 6 a.m. By 8.30 a.m., a team of Buddhist monks had placed his body on a funeral pyre at a nearby beach. Shortly before his death, he had written to his third wife saying that ‘the secret of life is knowing when to stop’.

Today, Watts’s legacy is studiously continued by his son, Mark. He is the director of the Alan Watts Organization and, together with five other employees, they digitise Watts’s extensive catalogue of lecture recordings. They are also responsible for licensing this content so that it can appear in adverts and podcasts and Netflix documentaries.

The organisation says on its website that it exists, in part, to protect ‘Alan’s material from over-use and monetization by profiteers’. The same material that was used in that cruise holiday advert. Mark Watts himself has appeared in a car advert, extolling the genius of his father while flogging the new Volvo X90. Those who wish to listen to the complete Alan Watts collection need only hand over $360. Or, if that appears too steep, you can instead purchase the ‘essential lectures’ for a mere $80. Much like Watts Snr, there’s something hucksterish about the whole enterprise. I don’t doubt the sincerity of his son – he has dutifully tried to preserve his father’s recordings – but he has also successfully made a career out of his father’s legacy.

For a man who bemoaned individualism, Watts’s treatment of his wives and children was staggeringly selfish. He seemed at times to see them as playthings and at worst irritating obstructions. Yet throughout his life, there is little sense of menace. He does not seem to have been a cruel man, only lost.

His real skill was a sort of easy profundity, one that appeals especially to young western minds chafing against the world. Take this section from The Joyous Cosmology, a book about how LSD helped Watts discover the link between western science and eastern philosophy, in which he criticised the:

compartmentalisation of religion and science as if they were two quite different and basically unrelated ways of seeing the world. I do not think this state of doublethink can last. It must eventually be replaced by a view of the world which is neither religious nor scientific but simply a view of the world.

The confidence with which Watts makes these grand philosophical statements is breathtaking. But sometimes this inclination towards sweeping statements ends up sounding absurd. Early on in his autobiography, Watts writes: ‘One of the major taboos of our culture is against realising that vegetables are intelligent’. He then goes on to tie panpsychism with evolutionary theories about the advantage of sweetness in fruit. It’s all brilliantly wacky.

His philosophy is also reductionist. Those things you thought separate and discrete are really just one and the same. It’s reassuring. Watts breaks down boundaries and tells the believer: things are simpler and more unified than you might think. And you are one of just a few who truly understand.

Yet his relationship with Zen Buddhism was almost as distant as the one with his family. Many current Buddhists now consider Watts’s understanding of their faith to be limited, even wrong in places. James Ishmael Ford recounts a lecture he attended with another Buddhist priest who was asked about Watts:

The priest sighed. Apparently he had heard this question before. And then said, ‘I know there’s a lot of controversy about Alan Watts and what he really understood about Zen.’ He paused. And then added, ‘But, you know. Without Alan Watts, I wouldn’t be here’.

That’s perhaps his real legacy. Watts managed to bring Zen Buddhism, however mangled, to the western world. It was through him that the casually interested were first switched on to eastern thought. But the tragedy of Watts was that in trying to avoid the horrors of stale old England, he became an early version of the new western man: more attuned to his own inner life and more unhappy because of it. Despite that, he managed to make a decent living. Only in the West can you drop out and cash in.