As far as the national press cared, Chicago’s 1990s indie-rock scene revolved around Smashing Pumpkins, Liz Phair, and Urge Overkill. I won’t say anything one way or the other about the merit of those artists, but their success had the felicitous side effect of persuading major labels to slosh irresponsible amounts of money around the city—and local labels, producers, and musicians used that money to do much more interesting things.

One of the local labels that arose in this environment was Kranky, founded in 1993 by Bruce Adams and Joel Leoschke. Like Drag City and Thrill Jockey, two of its best-known peers from that era, Kranky (styled “kranky” by the label) was uncompromising in its aesthetic choices—in fact, one of its early slogans was “What we want, when you need it.” Unlike those operations, though, Kranky stayed small. When the label matured in the late 90s, it was averaging just eight or nine releases per year—but its influence has long been hugely out of proportion with its size.

In the pre-Internet era, when albums had to be physically shipped, Chicago remained an important hub of music-industry infrastructure even as its other industries withered. Adams worked for a suburban distributor called Kaleidoscope in the late 80s (it also employed Drag City founders Dan Koretzky and Dan Osborn), and a few years later he befriended Leoschke while they were colleagues at Cargo, a major distributor of indie labels. Musicians often worked at distributors, labels, venues, recording studios, publicity firms, or college radio stations, and even if they didn’t, they knew people who did. This helped trigger an explosion of grassroots collaborations, with noise-rock players rubbing elbows with folks operating in avant-garde jazz, electronic dance, psychedelia, ambient music, and more.

Adams and Leoschke contributed to this wildly fertile hybridization by opening a door from indie rock into an almost otherworldly space—one that rewards “concentration, stillness, and the abandonment of preexisting structures and conventions,” as Jordan Reyes put it in the Reader in 2018. “Kranky debuted with Prazision, a beautifully glacial album by Virginia drone-rock trio Labradford,” he wrote, “and since then it’s maintained a focus on meticulous, entrancing sounds, sometimes understated and ghostly . . . and sometimes towering and awe inspiring.”

Labradford’s 1993 album Prazision, the first Kranky release, has proved enduringly influential.

Kranky began working with its best-known artists in the late 90s: it released three albums by Minnesota trio Low before their move to Sub Pop, and it issued the CD version of the debut full-length by Montreal collective Godspeed You! Black Emperor, F♯ A♯ ∞, followed by Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas to Heaven. But by then the label’s sonic territory—lush and caustic, serene and uneasy—had already been staked out by the likes of Labradford, Jessamine, Bowery Electric, and Stars of the Lid.

Bowery Electric helped define the Kranky sound with their 1995 debut album.

“At a certain point, an aesthetic started to congeal,” Adams told Reader critic Peter Margasak in a 1998 label profile. “I always think of it as the intersection where our tastes overlap with the economic possibilities of who we can work with.”

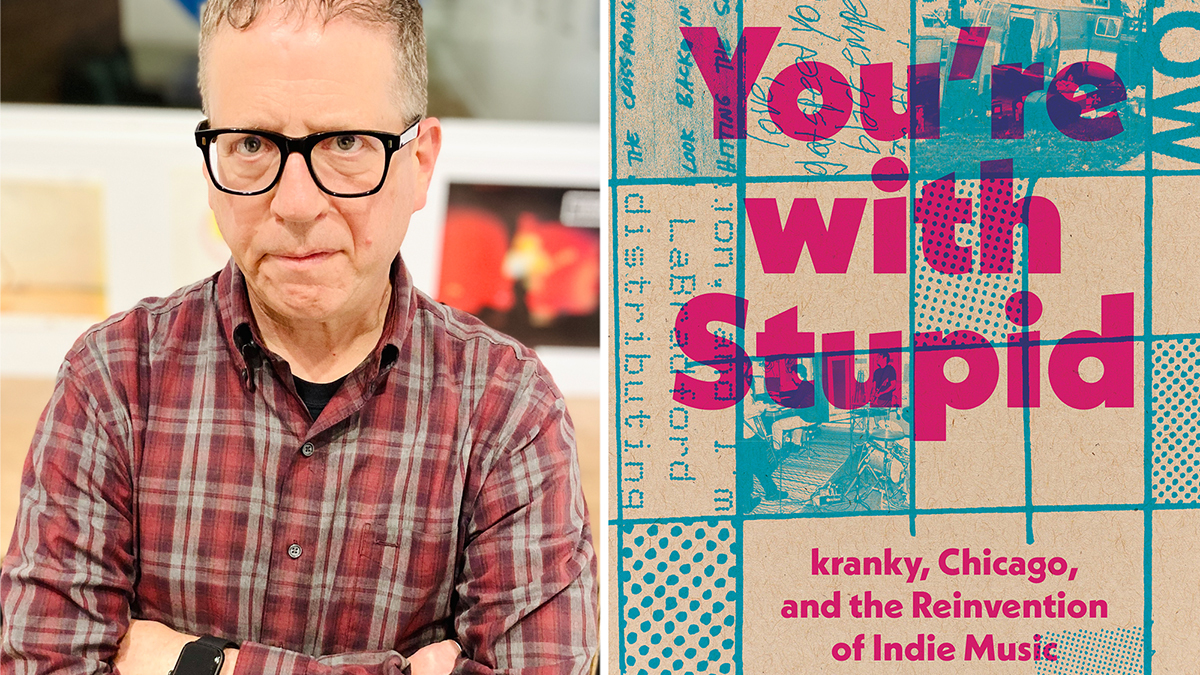

The label developed a distinctive personality too: austere, remote, and quietly, somewhat cryptically playful, with a sprinkling of what Margasak called “almost recreational negativity.” The title of Adams’s recent book about Kranky and its milieu, set mostly in the 90s and early 2000s, comes from another label slogan: You’re With Stupid: Kranky, Chicago, and the Reinvention of Indie Music.

Latter-day Kranky artists include Liz Harris’s project Grouper.

After Adams sold his share of Kranky to Leoschke in 2005, he ran a low-key imprint called Flingco Sound System for more than a decade. He now lives in Urbana. Leoschke is in Portland, Oregon, as is the Kranky warehouse. The label’s other staffer, Brian Foote, does management and promo work in Los Angeles. Kranky’s latter-day artists include Tim Hecker and Grouper.

This excerpt from You’re With Stupid (published by the University of Texas Press) is drawn from two different spots in the book. It sets the stage for the launch of Kranky and describes the community of musicians that Adams and Leoschke helped shape with their stubbornly idiosyncratic ears and prescient vision. Philip Montoro

From You’re With Stupid: Kranky, Chicago, and the Reinvention of Indie Music by Bruce Adams

The story of kranky is a Chicago story. In the early eighties, as a global music underground was developing, a network of wholesale music distributors, independent record labels, clubs, recording studios, college radio stations, and DIY publications established themselves in Chicago. The city had been a center of the recorded music business since 1913, when the Brunswick Company started making phonograph machines and pressing vinyl. Chicago had been home to jazz pioneers Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver, and Louis Armstrong for a brief, impactful time. In the 1950s Chess Records was a force in the blues and R&B scenes. Alligator Records was an independent blues label started in 1971. But the founding of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (or AACM) in 1965 is what created the precedent and working model for independent organization and avant-garde music in the city that eventually was reflected in house music and underground rock. AACM’s self-reliance and the border-crossing devotion of related musicians who incorporated ancient African music into the creation of future-facing music put Chicago on the map of innovative and independent music centers.

It was possible to get cheap apartments to live in or practice space for your band or even a storefront to open a distributor or store. The hollowing of the city’s industrial base had left empty warehouses and business spaces that were ideal for multiple activities, especially for anyone willing to live near a highway, train line, or in a low-income or overlooked neighborhood. One point of origin for house music was an underground club called “The Warehouse.”

The people behind the bars or record store counters, or piling the boxes up in warehouses, were often musicians, or artists, or both. Well-stocked record stores and distributors brought records into the city, giving people opportunities to listen to and process music. The radio provided access to multiple college stations playing a dizzying variety of music. Rent was cheap enough that people didn’t need full-time jobs and could pursue their enthusiasms. David Sims of The Jesus Lizard moved to Chicago in 1989 and recalled in the free weekly the Chicago Reader in 2017 that the band’s landlord “raised the rent on the apartment five dollars a month every year. When we moved in it was $625 a month, and when I left 11 years later it was $675 a month.” My experience was similar.

Stars of the Lid released their magnum opus—a three-LP album—through Kranky in 2001.

If you were a music lover but not a musician, you could work for a music-related business or start your own. Self-published fanzines popped up, and people had workspaces where they could screen print posters and T-shirts for bands. The major labels and national media were located on the coasts, lessening the temptation for bands to angle for the attention of the star-maker machinery. The circuitous impact of all the above was meaningful in shaping how and why Chicago would become the fertile center of the American indie rock scene, and why it produced so much music that broke the stylistic molds of that scene.

I moved to Chicago from Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the summer of 1987. I shared a house with a roommate from Michigan in a northside neighborhood called Bowmanville and started work in a suburb called Des Plaines, right by O’Hare. It was at a distributor called Kaleidoscope, run by the unforgettable Nick Hadjis, whom everybody called Nick the Greek. His brother Dmitri had a store in Athens and promoted shows for American bands like LA’s industrial/tribal/psychedelic outfit Savage Republic. Kaleidoscope was a common starting point for enterprising young music folks seeking to enter the grassroots music business within Chicago. People came in from downstate Illinois or Louisville, Kentucky, or Austin, Texas, and worked there before they went off into the city to work at the growing Wax Trax! and Touch & Go operations. Bands were starting their own labels to record and release their music, following the pattern established by the SST and Dischord labels. In those pre-Internet times, scenes grew up around successful bands who distributed their singles via touring the country, getting fanzine coverage, and garnering college radio airplay. The seven-inch single, LP, and tape cassette were the preferred formats for these bands and labels.

Kranky coreleased Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s debut album with the Constellation label.

Two guys named Dan (Koretzky and Osborn, respectively) who worked at Kaleidoscope had been impressed, and rightly so, by a self-released, self-titled album by the duo Royal Trux that Kaleidoscope stocked. A little later, I had a single called “Slay Tracks 1933:1969” self-released by the band Pavement firmly pressed into my hands by one or another Dan and was informed that only a thousand were pressed. I bought it that day. Dan Koretzky and Dan Osborn each worked at the distributor, had experience at Northwestern’s WNUR radio station, and were strategically placed to discover and make contact with new bands. They reached out to Royal Trux and Pavement, started a label called Drag City in 1988, and began releasing records in 1989. In a similar process, Joel Leoschke and I would start kranky after hearing the first single from an unknown ambient duo from Richmond called Labradford four years later.

Low were one of Kranky’s other best-known signings.

In the economic sense and at the label level, independent or “indie” refers to a means of production and distribution. Independent labels operated outside the fiscal control of major labels and multinationals that owned them; the so-called “Big Six” of the Warner Music Group, EMI, Sony Music, BMG, PolyGram, and Universal that operated from 1988 to 1999. Indie labels arranged and paid for manufacturing themselves and were distributed at least in part by independent distributors like Chicago-based Cargo, or Mordam Records in San Francisco, who sourced records from hundreds of labels around the world and got them into record shops domestically.

The levels of economic independence labels exercised were on a spectrum. So, for example, hardcore punk records on the Washington, DC, Dischord label were manufactured by the British independent distributor Southern Records, which also provided European manufacturing and distribution for a consortium of mostly British labels. Although Chicago-based Touch & Go Records were also distributed by Southern in Europe, the label arranged and financed its own manufacturing. By necessity, most labels had to interact with multinationals, and those interactions also existed along a spectrum. The psych pop Creation label, home to My Bloody Valentine and Oasis, and grindcore pioneers Earache Records with Napalm Death and Godflesh started out as independents in England and were eventually manufactured and distributed in North America by Sony. RED, originally an independent distributor called Important, was eventually acquired by Sony. Virgin/EMI Records opened Caroline Records and Distribution in 1983 in New York. Touch & Go was distributed by both of these distributors.

On Kranky’s early roster, Jessamine stood out as one of the more rock-leaning acts.

Labels turned artists’ recordings and artwork into LPs, singles, cassettes, and compact discs. Parts were shepherded through the manufacturing process, and finished products were received and warehoused somewhere, be it someone’s closet, basement, or a wholesale distributor, and then scheduled for shipment to record stores and mail-order customers. Stores needed to know what was arriving when in order to predictably stock their shelves, and so release schedules had to be created, coordinated, and adhered to. Likewise, fanzines, the magazines created by dedicated fans/amateur writers, and radio stations had to be serviced with promotional or “play” copies of releases so that reviews were run and music was played on air when records arrived in stores or as close to that time as possible. If there was enough money available, advertising would accompany the release. Some labels had paid staff or volunteers who promoted records; others hired agencies. If bands were touring, stock had to be ready for them to sell on the road. And if a label wanted to export releases or had a European distributor, the schedule had to be aligned with the logistics of overseas shipping and sales. At any step in the process of releasing music—manufacturing, shipping, or distribution—a label could easily find itself doing business with a multinational. Complete self-sufficiency and independence for record labels was virtually impossible in practice. It’s fair to say that the greater the degree of economic independence a label possessed, the more aesthetic leeway it had to operate with.

There was something about the Chicago music scene that is harder to quantify, but definitely existed: an attitude of mutual support and aid. When I worked at Kaleidoscope, my coworkers were in bands like Eleventh Dream Day and the Jesus Lizard. At Cargo, many of the employees were in bands and would show up at each other’s shows to lend support. This was, to some extent, an inheritance from the early days of the hardcore punk rock circuit, when bands had to depend on each other to organize and pull off shows. I had seen the ethos in action when I roadied for Laughing Hyenas and saw how they coordinated with the Milwaukee band Die Kreuzen to perform together in weekend shows across the Midwest. This do-it-yourself, or DIY, approach worked for sound engineers like Steve Albini and John McEntire who had begun as musicians. As David Trumfio puts it, “Touring and meeting other people on a similar path was very important to keeping my focus. Being a musician is and was essential to being a successful engineer and/or producer in my opinion. You have to have that perspective to know how to relate to the people you’re recording.” As groups returned to Chicago from touring, they offered reciprocal aid to bands they played with in other cities. Tortoise provided space in their loft to Stereolab, and Carter Brown from Labradford sold equipment to Douglas McCombs from Tortoise. In Chicago, musicians performed and recorded together, crossing over genre boundaries to interact. Tom Windish summarizes it by saying, “It wasn’t like the Touch & Go people couldn’t be friends with the Drag City people or the Wax Trax! people couldn’t be friends with the Bloodshot people.” Brent Gutzeit, who came to Chicago from Kalamazoo, Michigan, in late 1995, describes the scene: “Everybody was jamming with each other. Jazz dudes playing alongside experimental/noise musicians, punk kids and no wave folks. Ken Vandermark was setting up improv and jazz shows at the Bop-Shop and Hot House. Michael Zerang set up shows at Lunar Cabaret. Fireside Bowl had punk shows as well as experimental stuff. Lounge Ax always had great rock shows. Empty Bottle used to have a lot of great shows. I set up jazz and experimental shows at Roby’s on Division. Then there was Fred Anderson’s Velvet Lounge down on the southside. There were underground venues like ODUM, Milk of Burgundy, and Magnatroid where the no wave and experimental bands would play. Even smaller independent cafés like the Nervous Center in Lincoln Square and Lula Cafe in Logan Square hosted experimental shows. There was no pressure to be a ‘rock star’ and nobody had big egos. There was a lot of crossover in band members, which influenced rock bands to venture into the outer peripheries of music, which provided musical growth in the ‘rock’ scene.”

Kranky has worked with a few Chicago projects, among them Robert A.A. Lowe’s Lichens.

Ken Vandermark breaks down the resources and people who made Chicago such an exciting city to be in: “A combination of creative factors fell into place in Chicago during the mid-’90s that was unique to any city I’ve seen before or since. A large number of innovative musicians, working in different genres, were living very close to each other. Key players had been developing their ideas for years, and many were roughly the same age—from their late twenties to early thirties. A number of adventurous music journalists, also in the same age group, were starting to get published in established Chicago periodicals. People who ran the venues who presented the cutting-edge music were of this generation too. Music listings for more avant-garde material were getting posted effectively online. All of this activity coalesced at the same time, without any one individual ‘controlling’ it. And there was an audience hungry to hear what would happen next, night after night.”

Bill Meyer sees this cooperative spirit from the independent scene of the mid-1990s in present-day Chicago: “I describe it as an act of collective will. This thing exists because it does not exist in this way, anywhere else in the world. What we have now are people who really want to get together. They will rehearse each other’s pieces and they will be in each other’s bands. They don’t resent each other’s successes. If you go to New York, there’s a lot of people doing things, but there’s also a lot more hierarchy involved. You don’t have that here. And I think that to some extent, the Touch & Go aesthetic imported over into the people who came after Ken Vandermark and were very attentive to that kind of thing.”

Kranky has been around long enough for its newer artists to be influenced by the label’s early output.

In Chicago, 1998 was a year of significant releases from Tortoise, Gastr del Sol, and the Touch & Go edition of the Dirty Three’s Ocean Songs. The latter was an Australian band made up of violinist Warren Ellis, drummer Jim White, and guitarist Mick Turner. Their fourth album was recorded in Chicago by Steve Albini and is one of the most accurately titled ever. Ocean Songs ebbs and flows with the trio’s interplay and became very popular with rock fans who may have been familiar with the Touch & Go label but were otherwise unenthusiastic about the new bands in Chicago. In performance, the Dirty Three were dynamic, with Ellis being particularly charismatic. White moved to the city and contributed to the Boxhead Ensemble and numerous recording sessions. Drag City released Gastr del Sol’s Camofleur, solo records from Grubbs, and a triple-LP/double-CD compilation of Stereolab tracks called Aluminum Tunes. Thrill Jockey were channeling the Tortoise TNT album through Touch & Go Distribution.

The Chicago scene was producing an incredible range of music. Lisa Bralts-Kelly observes that unlike earlier in the decade, when groups moved to Seattle to make it as grunge stars, “Nobody came to Chicago to sound like Smashing Pumpkins or Liz Phair.” And unlike centers of the “industry” like New York City and Los Angeles, prone to waves of hype that focused on a few bands, as occurred with the Strokes beginning in 2001, a multitude of Chicago bands could develop, connect with supportive labels, and build an audience.